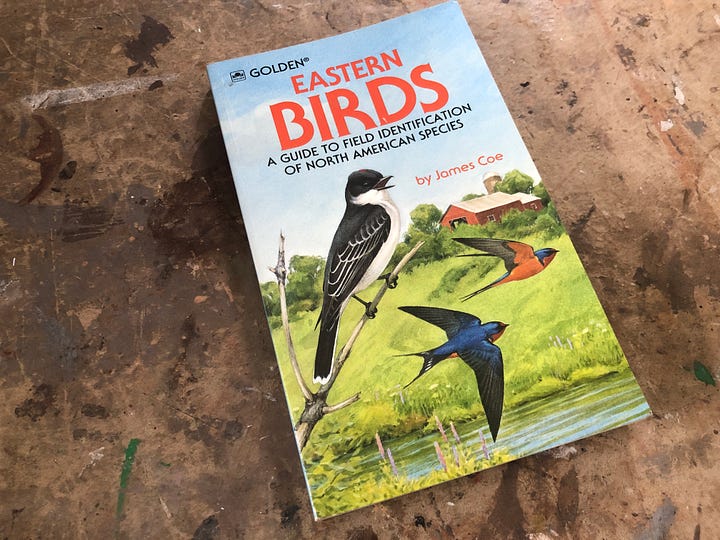

Beakuency welcomes Jim Coe, a landscape painter based in Greene County who is passionate about birds. He is the author of The Golden Guide to Field Identification of North American Species. With his professional training in biology and extensive birding experience, he accurately captures not only birds themselves, but also the time spent observing them in the Hudson Valley and beyond. In this interview, Jim shares his career and artistic process that enables him to create such iconic images. He says he "hopes to evoke the poetic quality of birdwatching, capturing that magical moment when the bird, its environment, and the atmosphere merge into one memorable image." His paintings invite us to appreciate these magical moments and the beauty right around us.

Jim Coe website: https://jamescoe.com/

This interview was recorded on July 9, 2025 and broadcast on Wave Farm’s WGXC 90.7FM on July 26, 2025.

Interview Transcript

Mayuko Fujino: Could you briefly introduce yourself?

Jim Coe: Yeah. My name is James Coe, although everybody calls me Jim. So Jim Coe, a bird artist and a naturalist. And earlier in my career I was a field guide illustrator, although I'm now an oil painter, a gallery painter. And I do landscapes and birds in the landscape.

MF: Your interest in birds began in your childhood. I read it in your bio that you taught yourself how to identify birds. How old were you in the first place?

JC: I was about, I guess, 12, 13.

MF: Okay, so not like [very] little.

JC: No, no. Kind of a young teenager and I had a friend across the street and he was interested in natural things. And we would ride our bicycles around town just exploring. And birds caught my eye.

MF: And this is in New York City?

JC: It's in the suburbs of New York City, in Westchester county, in Larchmont. And actually, the place where we used to go, there was an old dump. And we would go to the dump looking for junk. But it was next to a marsh. And when we'd be exploring the dump, you could see into the marsh and there were egrets. And then there were these other birds that I learned were Yellowlegs. And they just intrigued me. And so he and I started paying attention. We had field guides. And as I think I said in my bio, we started — he was from a very artistic family, I was not — and we got interested in the idea of drawing the birds and maybe making a field guide for ourselves. And so we started copying pictures of birds from other books. And I had never done anything artistic really, and it was not so much, we never finished the guide, it never came to anything, but it was the process of learning and exploring the possibility of drawing and realizing that I had some talent for it.

MF: I guess in those days parents let you run around on your own.

JC: They did. We would get on our bicycles. The dump was about a mile from the house maybe, and we would just explore anywhere we wanted to go and get into all kinds of stuff.

MF: That's how sometimes people grow their talent organically.

You know, a dump seems to be often a good place to watch birds.

JC: Today they still are. Like landfills are places that seem to attract. I think there are birds coming to feed on the food, the junk food. And then once you get those birds, the scavengers, you get the predators coming in there and you get a whole range of birds.

MF: It's really funny that it's sometimes even more productive than some nature preserves. You'll see a lot more stuff. And so that's funny. Your birding career started in a dump in the childhood, kind of.

JC: Yeah, I never really thought of it in those terms, but yeah, I guess it started in the dump. [laughs]

MF: I wanted to ask you about the field guide you compiled with your friend that you just mentioned. And so you said you never finished it.

JC: No, we never even got very far along. We did maybe half a dozen drawings each. And, you know, kids at that age, you move on to other things. But realizing that I had the skill to draw and then to mix colors and to render things so that they looked real was kind of a real discovery. And I started doing watercolors and got into gouache paints and started doing paintings of birds.

MF: Right. You mentioned your grandfather gave you an oil painting set.

JC: When I turned 16, I had already been drawing for a couple years. We started with colored pencils. That was the medium we started with originally for the field guide. Because that's what we had. Everybody had a little set of Venus colored pencils. And then my grandfather gave me a set of oil paints when I turned 16. And that night my parents had a party downstairs and I had a record player and I put a record on repeat so it would just keep going over and over. And I set up a still life and I did a painting in the hours that I had to myself that night. And again, I kind of amazed myself because I didn't know I could do anything like that.

MF: Yeah, because you said your family was not particularly artistic type.

JC: No, no, not at all.

MF: Just natural to you.

JC: And also, we didn't go camping, we didn't go for hikes. Discovering birds in nature was something new to the family as well.

MF: Very interesting. So it just all came to you naturally, maybe your friend’s influence was really big, I guess.

JC: And then, I have a younger brother and had an older brother, and I got them both interested in birding.

MF: Do you guys bird together?

JC: We do. My younger brother just recently moved into this area and we bird watch together.

MF: Wait, you were with him when… ?

JC: Yes, I was with him when I met you. That's right. When I met you in Catskill.

MF: That's very nice.

JC: He's been my bird watching companion now for 50 years or more.

MF: That's really sweet. So your interest in both birds and art kind of started in childhood and then you went to Harvard to study biology and ornithology. And so you have that professional background. And then you went to get professional training as an artist.

JC: Right. By the time I went to college, I had more or less self taught myself how to illustrate birds. I knew watercolor, I had painted in oils, I could do gouache. And during the years I was in school, I sent my work to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that had a, it's now called the Living Bird that they send out to their members, but back then it was an annual journal that the lab published. And the editor of that journal was very open to having young starting artists send artwork. And so he published a few of my drawings. So that was a big boost, realizing that I could get my work published. During the years I was in school, I was a little embarrassed by my interest in birds and bird watching because nobody else was a bird watcher back then, especially no girls were. [laughs] So I focused on the biology and focused on getting my degree in the biology and studying birds and did a little during the summer months I would spend time painting birds. And then when I finished, I decided I wanted to be an artist instead of pursuing biology and going to graduate school and becoming an ornithologist. So I got a job just to pay the rent in a bookstore. And I would paint all day long and work at night and paint all day long in a little studio in my apartment.

MF: And then that eventually led to your work as publishing this field guide that you were talking about? How, if you can tell us how that happened?

JC: The first book that I worked on was a Field Guide to Birds of New Guinea. And that connection was made through my advisor at Harvard, who was the ornithologist on the faculty there. And he knew somebody who had studied with him who was putting together a field guide and looking for artists. And so he made that connection for me.

My own field guides happened later on after I moved to New York and I was involved with, I was in art school in New York, but I was still working on the New Guinea guide. And I would take my paints and my boards and all my materials. I would take them to the Museum of Natural History because I needed the specimens at the museum to work from for that guide.

And while I was there, I met all kinds of ornithologists who came through that department. And so I met John Bull and he and his wife hired me to illustrate a field guide of theirs. I met Guy Tudor, who advised me in terms of being a field guide illustrator. I re-met Al Gilbert, another illustrator, who connected me with another guide that was being done during the years I was in art school. So it was through personal connections. And then eventually a family friend who was in the publishing industry, had been a publisher himself, hooked me up with Golden Books, and they were looking for a field guide. And so I made a proposal to write and illustrate my own field guide for them.

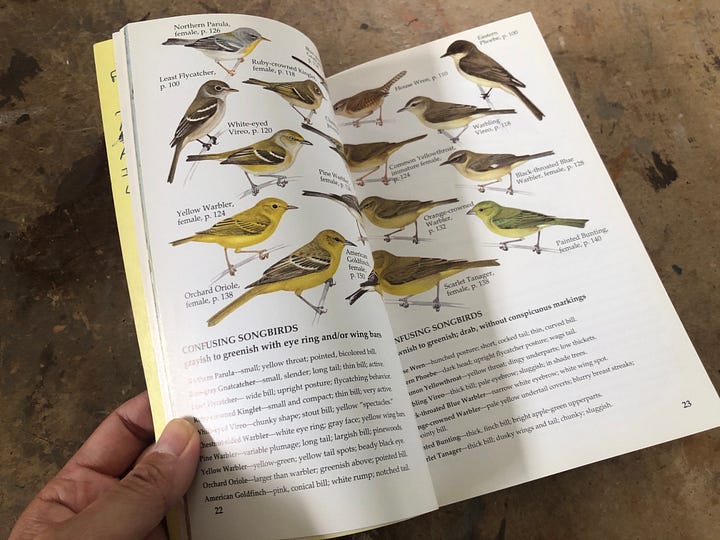

MF: Well, what I imagined was that the field guide artists would face challenges decid[ing] what “the typical” of each bird looks like. Because, colors can be very tricky, watching them in the morning versus in the evening or a cloudy day versus sunny day. And then individuals have differences. I still get tricked by individuals all the time by the variation. And so you [as a field guide artist] have to come up with this one figure that gives you the idea of what it generally looks like. I was curious how you’d decide that this is THE look of Canvasback or whatever ... I'm looking at a Canvasback in your book now.

JC: Yeah. Well, part of it is, you know, some of the guides — I think there's been a tendency for field guides to become more and more comprehensive. And like David Sibley's book, which is many times the size of mine and has many more pages, he does show the range of individuals. He'll have a worn one versus one that's freshly in a fresh plumage, or he'll have a juvenile and an adult female and adult male. He'll illustrate maybe half a dozen of one species.

In my book, which was abridged and designed to be very small and compact, I really did have to find just one example to represent the whole species. And I think part of it is just my experience as a birdwatcher. I know what the typical is. By the time I did this, even then, I had been bird watching for 15 years, and I knew what the typical example was. You know, looking at photographs, going and looking at museum specimens. You get to know the birds intimately from bird watching. And you know what the typical one is, I think. You just have an instinctive feel for what the typical, say Song Sparrow, it's a very varied bird, but you know what your typical Song Sparrow looks like.

MF: Song Sparrows are just so varied.

JC: They are. And especially across the country, they're even more varied. Like in the Pacific Northwest, they look totally different and they sound different than ours here in the Northeast.

MF: I just saw a post by the Cornell Lab [of Ornithology, about] all different variations of Song Sparrows.

JC: That's right. Their Newest issue of the Living Bird has a great article all about Song Sparrows and showing the range of the species across the continent.

MF: And as I'm looking at this list, I'm like, [even only] within Columbia County, I get confused all the time. Sometimes it's so rusty that I get excited [thinking] oh my god, it might be Fox Sparrow. And then, it's a Song Sparrow.

JC: I mean, I think as a bird watcher, the more familiar you are with the range of species, you learn that there is individual variation in plumages, but you start to notice different things. You start to notice shape and structure as much as you would notice plumage. So a Fox Sparrow, you wouldn't confuse with a Song Sparrow because you start to realize that it's built differently, it behaves differently, it's got a real big, fat, chunky body. And as a bigger, chunkier bird, it just moves differently. And so you start to notice these very subtle things. And so when you put together a field guide, as you were saying, you want to represent those differences in structure, posture, behavior with just one illustration, and it is a real challenge to put together a field guide plate where you have one quintessential example for each species.

And then the other thing that you do when you put a field guide plate together is that you have to kind of arrange your plate and pose the birds in a way that a beginner can look at it and see the differences before they look in to see the details. They see just the shape differences or the posture. So here a Song Sparrow and a Fox Sparrow, they're in very different poses, but typical of what you see when you see each of those birds.

MF: Every time I take a picture of Song Sparrow, it's pretty much this. [points at the Song Sparrow illustration in Jim’s field guide.]

JC: Exactly. And every time you see a Fox Sparrow, they're mostly on the ground doing that [points at the Fox Sparrow illustration on the same page.] And so that was the challenge of putting together a guide, coming up with not just the plumage that represents the full range, but a posture, a gesture that kind of indicates the behavior and the character of the bird.

And that's why I think a field guide with an artist's illustrations is more effective and a better learning tool than some of the newer guides that have photographs. Because photographs so often don't capture the right pose or the right gesture or the lighting is different from one photo to another. And they're assembling them on one page. But the artist has the control to get the poses all comparable and yet indicate those subtle distinctions.

MF: One photo captures that one unique moment of that unique individual. Whereas this is like an archetypal Song Sparrow.

JC: You said it better than I did. Archetypal is the right word.

MF: That was really the impression of your landscape painting too, that I want you to discuss more about. Your landscape paintings featuring birds perfectly capture the essence of both the birds and the feeling of being in that space with them. And I mentioned in my email to you, I participated in the Winter Raptor survey for the last two years. So every week I get to go out and see the winter field and, you know, a little different weather, different light because the time of sunset changes every week. How many Northern Harriers we see is different, Short-eared Owls show up or not, every week it's very different. But there's this, you know, feeling of being in that cold air and seeing these birds foraging. And that feeling, I've become, I think, familiar with that by doing it for two winters every week.

And so when I saw your paintings, particularly of that the Northern Harrier foraging in the winter field (titled Snow on the Hayfields), I don't know which winter field it was and this is not the harrier that I saw, but it's all there, that very feeling. And so I was wondering if your training as a field guide artist contributed [to] your skill to capture that exact feeling of, not just the bird this time, but the whole experience of being with the bird.

JC: I think my experience as the illustrator allows me to have the freedom because I know the birds so well and I've drawn all of them so many times and that I can very fluently draw a bird and put it in the proper context in the landscape. So I think my experience as the illustrator gives me the freedom to introduce birds into my landscapes. And they feel very natural. They don't feel imposed or artificially introduced. And I think that's where the two parts of my career have kind of worked together. But as a landscape painter, because I paint outside sometimes or I start many of the paintings outside, they get that feeling of being in the experience because they are coming from that moment that I'm out there or the hour and a half that I'm painting outside.

MF: So in practice, you go outside and then you sketch out the landscape. Birds are not necessarily in the spot where they end up in your painting. But you kind of know where they should be in this landscape [that you’re painting]?

JC: Well, let's talk about the one that we're looking at here, [points at one of his paintings on the wall] of the Killdeer on the edge of a winter creek with some sunlit grasses next to it. This creek is a real place. It's about a mile and a half away from here. And I take walks down there sometimes in the winter with my camera. And it was too cold to paint on the day that I saw that. But I had my camera with me, and I saw the sunlit grasses on the edge of the creek with the mud behind it. And I was really intrigued, and I took photographs of it. I came back and I did a painting of that tuft of grass with the sun on it. I didn't even think of putting a bird in it at first. I was interested in the reflections and the grasses and the light and the warmth of that winter light. You know, when it's so cold, you get that warm February light. I just love it. It wasn't for several years that I looked at that scene and I thought that would be a good place to put a bird. And I thought about it for a while and let the idea sit in my head before I thought of… first I thought of maybe a heron, but then the heron, a Great Blue Heron, you might see there in the winter, but the heron is going to tower over the grass, and it's going to be a different relationship, proportional.

And then I thought of a Killdeer. The Killdeer first was going to be over to the right side of the painting, where it was kind of fully in the light. Knowing the Killdeer well, I can put it in, take it out, put it in, take it out, and it's not a big deal to have to repaint it because it's just right there. It just flows out of my brushes when I paint a bird. It's much easier than the landscape, actually. And so then my idea was to tuck the bird in behind the grass where the shadows of the grass are falling over the bird. And then it becomes part of the experience, part of the scene. By having those shadows cast across, and the light across the bird, it integrates it into the scene. And it becomes part of the full experience, as opposed to an illustration of a bird kind of separate from the grass.

MF: Sometimes when we go birding, when people have knowledge of [birds’] behaviors and habitats, they have some ideas of where we [would] very likely see a certain species and where we [would] see in the spot. [For example] Indigo Bunting tends to be at the very top of a tree, singing. And that's sort of what we picture when we think of Indigo Bunting. When I didn't have that knowledge, I started learning from what people are saying that you're likely to see certain things in this particular spot. You can maybe exercise that knowledge in painting. [Although] sometimes you [could] get surprised by weird individuals in unlikely spots.

JC: There's always surprises. But I think really sharp and experienced birdwatchers approach it exactly as you just described. When we go out, we know what birds might be in a certain habitat. We know how they behave, we know where to look for them. We know if you're looking for a Veery or a thrush, you know, to look down because it's going to be on the ground. Bunting is going to be singing from the top of a branch, or tanager also is going to be at the very top of a tree at this time of year when it's singing. It allows us to find things much more readily than a beginning bird watcher because we know what we're looking for and where to look for it.

MF: So that's sort of the experience that you apply when you paint a landscape with a bird in it. It's not just the anatomical, biological knowledge of birds that you have, but also the experience of being there, seeing them in the field.

JC: So many of my paintings that I do of a bird in the landscape, kind of, as I was explaining to you with the Killdeer painting, it starts with the landscape, and then I feel like the landscape needs something else or it needs a focal point to make it more interesting, or maybe it doesn't need it, but I want it to have a focal point and then I'll add a bird to the landscape. And so often, because you want the bird to feel naturally in the landscape, you wouldn't see a little [bird] in a big, broad landscape. Or like the big field that you brought up before, the winter hay field, there's probably Song Sparrows or Snow Buntings or Horned Larks or Savannah Sparrows in that same field, but you're not going to see them. Or if you do, they're just going to be a little speck.

And if you want to add an element, a bird element to the painting in a way that feels natural, it has to be a larger scale bird that you would actually notice in the context of the scale of the scene. And that's why a harrier or a Red-tailed Hawk is an appropriate bird or why Great Blue Herons end up in so many of my paintings. Because they're big and you notice them and they're part of the landscape as we see it without binoculars. Because I'm not using binoculars when I'm looking at the landscape for a painting.

MF: And that's pretty much how the real feeling of birding, that's how it feels when you're in the field, we're enjoying looking at these little dots in the landscape.

JC: I think I described this painting to you… [picks up a painting]

MF: Oh, the [Common] Yellowthroat.

*This is the painting Jim is holding in the photo at the top of this article.

JC: Yeah, I actually have it right here to show it to you. Here is a scene, this was over at Olana [State Historic Site]. I was down there painting at Olana and I painted the shoreline and the cattails just coming up in early spring. And I have another painting of this that was very successful as a landscape painting with no bird. But then I looked at it and I thought, well, that's such a nice evocative scene. You should be able to tuck a bird in there. And so I thought of various different birds I could stick in. I thought of having a Mallard swimming in the background, which is something I may still do. But I thought I'd put a Yellowthroat in. And as you can see, it's tiny relative to the scale of the painting. And I would have to do the painting to make it a more comfortable scale. To paint that Yellowthroat, the painting would have to be at least twice the size. And as I worked on this, I kept rendering the bird too large and it didn't feel like it was the right proportion in nature. So I had to keep making it smaller and smaller.

MF: I thought about the [American] Woodcock painting that you did (“Woodcock Sky”) which you have to really look closely [wondering] “Where is the woodcock?”

JC: And that's a large painting. That painting is almost four feet wide, over three feet wide. And the woodcock is maybe three eighths of an inch. It's just a tiny little thing.

MF: But that's exactly how it feels when you actually go out and try to “see” a woodcock. I mean, you hear it. Because of the New York State Breeding Bird [Atlas], they encourage you to learn the breeding behavior, and so me and Pat [Gubler, also present in the room] learned, watched a video of what we’re supposed to look for…

JC: When you're out looking for woodcock.

MF: Yes. The sound of it and how they fly. And then we went out and looked for it, and we actually found it, and we got to hear it.

Pat Gubler: It's like textbook behavior.

MF: Just like in the YouTube video!

JC: I actually did three or four versions of that painting that you refer to. It's kind of a sunset scene of some fields, and it's mostly sky with clouds and sunset sky. And a couple of them don't have the bird at all. And I titled them Listening for Woodcock. So it's all about that experience. And then I decided, well, maybe I can put, you know, put the bird in. But the painting works with the bird or without, because it evokes that moment of being out there in March at that time of day.

MF: Totally does. The beautiful pink and the purple in the sky and how the woods are just so shadowy. It's exactly how it feels to be in the field trying to “look” for a woodcock. And I first thought that maybe you didn't put [the bird]. And then I found it in the shape of the woodcock. That's exactly how it feels.

JC: But there, too, the version that doesn't have the bird is much smaller. And I realized that to keep the bird proportionate to the landscape, it was gonna be just a little speck. And so I had to make the painting larger and larger in order for the bird to be visible and yet proportional to the scene.

MF: You know, sometimes it's a hard sell, like when we — I'm a member of the Alan Devoe Bird Club in Columbia County, and I'm sort of participating in organizing bird walks and stuff with other members. We get excited by even, not seeing it, but by learning, hearing songs. Or like you said, seeing a speck of it is enough for us to be entertained. But to organize a public walk to sell that experience as fun? It's a little hard [to] sell.

JC: Yeah. Especially woodcock, because it's frustrating. You hear it, you don't see it. You're cold. It's getting dark.

MF: Right. So it's such a joyful experience, but I sometimes wonder how you can convey those joys. You know, bird banding, it's really great. People get to see the birds right in their own hands, and that's a really great way to hook people in. But eventually people have to grow into this next step of getting excited by the speck and being in the space with the birds and appreciate that beauty. And your biography on the website says you “hope to evoke the poetic quality of bird watching. That magical moment when bird, environment, and the atmosphere merge into one memorable image.” If you can appreciate such moments and how unique each moments are, you know, to have that mindset really helps you appreciate that the world is so full of wealth. [It] really depends on you having that sense of appreciation. And I really feel that because I spent a big chunk of my life having mental health issues, and I couldn't quite function. Going outside and enjoy what's right in front of you was difficult for me for a long time. And then [I] eventually kind of learned from people who are into birds and then realize that even in a place like New York City, you get tons of different things if only you are able to see them, quite literally. You realize, “my god, how come I never noticed this before?”

JC: Well, I think part of it is because I became interested in birds at such a young age. And then actually there were two summers when I went up to Vermont with the Student Conservation Association to help. The first summer I was with a group of other high school students. We built trails and did things. But being in the woods and taking long walks myself and listening for different birds, knowing the birds and learning nature and learning to identify plants and being in nature, all became part of how I experienced the world during those summers. And today, if I'm outside or if I'm outside with my paints and I'm painting a landscape, I don't bring my binoculars with me when I paint the landscape because that would just distract me. I don't bring my binoculars, although I do bring my camera. But even though I don't have my binoculars, I hear every bird I'm there painting, and I'm clicking them off in my head when I hear them. If I'm at a field, I hear a Bobolink, I hear a Song Sparrow, I hear a Savannah Sparrow, I might hear a Meadowlark. I'm ticking them off in my head. And so it's still, it's just the way I experience the world as I hear those birds. It's part of Just being outdoors, the world of birds is part of my world.

MF: I think you painting these things capturing those magical moments in the way that people can learn from you that there are such magical moments exist right in front of us. You don't have to pay, you know, $5,000 to go to Disneyland to experience some magical moment. It's like, it's right there.

JC: And you also don't have to pay $5,000 to go see an exotic bird in some exotic country. There's wonder right here in our own backyard.

MF: Yeah. You mentioned you have more and more paintings of common birds lately.

JC: Painting common birds, things that I see here. The painting here of a Pileated Woodpecker, it’s one of my all time favorite birds. I've done a number of them. There's another one over there which was a study for the big one. This painting was about the bird, but it was more about the tree. Because when I would take a walk up the road, this tree was right on the edge of the road. And my wife and I would take afternoon walks up the road and we'd pass that tree and I noticed it, and I'd noticed that the bird was working on it, and you'd see chips on the ground. So you knew the bird was busy excavating. And so it really became a painting of the tree. And then I figured out how to bring the bird into the painting.

MF: I think it would be nice if people can learn — they may not become a professional painter, but they can activate their inner Jim Coe just to enjoy what's out there and be appreciative of what's right in front of your face. Because I can tell how different my life before learning how to watch birds versus after. And so I appreciate you making all these paintings. I mean, this is not a field guide, but kind of a guide into this mindset of seeing that magical moment.

JC: Thank you. And I think that little comment I made on my website talking about what I do in terms of trying to capture that magical moment, that is what I want to convey in the paintings. And if someone else can sense the magic that I feel when I'm creating that painting, then that's kind of the message I want to send with the artwork.

MF: Where can people see your work and how can they learn more about it?

JC: Well, I exhibit in galleries and museums around the country in various shows. But I have three galleries that carry my work in the Hudson Valley. There's the Mark Gruber Gallery in New Paltz, the Laffer Gallery in Schuylerville, which is up near Saratoga, and the Albert Shahinian Fine Art in Rhinebeck. And then I have a website, jamescoe.com.

MF: You were going to have a show in Vermont. That's happening right now?

JC: There's an art center in Vermont that I'm on the board of called the Monument Arts and Cultural Center in Bennington.

MF: Okay. And that's open to public?

JC: That is open to the public. It was closed for a number of years, so we're in the process of trying to get it back on firm footing. But it's a beautiful exhibition venue, and there's a show that's opening this coming weekend of the Society of Animal Artists. And I have three paintings in the show.

*For more information about this show visit: https://www.monumentcentervt.org/animalartists

MF: For how long?

JC: It will be up through the end of October.

MF: Okay. So it's a little bit far, but people can totally drive up to Vermont.

JC: It's about an hour and a half.

MF: Okay. It's not that far. Well, thank you very much.

JC: You're welcome. Thanks for coming to the studio.