Birds survived the mass extinction event 65 million years ago, and continue to thrive today. They are incredibly adaptable to the changes of their environments, using many strategies, such as altitude migration, finding new habitats, and genetic mutation in response to catastrophic events.

The ornithological collection at the Columbia-Greene Community College Natural History Museum helps us see how birds adapt and resist, and inspires us to follow their path of resilience. In this interview, Bill Cook, Claverack native, Professor Emeritus of Ornithology, and Curator of the Museum’s Ornithological Collection, shares insights into the adaptations of the birds featured in his writings and the collection, as well as changes he has observed in Hudson Valley bird populations through decades of birding.

Bill is not only an expert birder but also a dedicated supporter of the Hudson Valley birding community. For over 50 years, he has helped others improve their birding skills and pursue careers in environmental fields. He shares stories of those whose paths have crossed with his over the years.

On February 10, 2024, the public was invited to the museum’s open house, hosted by the Alan Devoe Bird Club of Columbia County. Chris Franks, the club’s coordinator and expert birder from East Chatham, joins the conversation to discuss the event and the impact of Bill’s collection on the scientific study of birds.

Columbia-Greene Community College Natural History Museum

www.columbiagreene.edu/academics/natural-history-museum-2

This interview was recorded on January 18, 2024, and broadcasted on Wave Farm’s WGXC 90.7FM on January 27, 2024. The transcripts have been edited for accuracy and clarity, with minor additions made in collaboration with the interviewees.

Interview Transcript

Mayuko Fujino: Could you briefly introduce yourself?

Bill Cook: My name is Bill Cook. I’m currently the curator of the Natural History Museum at Columbia-Greene Community College. I’m a native of Columbia County. I was born in Claverack. I have a Ph.D. in ornithology, and I taught general biology and other courses at Columbia-Greene for many years, nearly 50 years.

Chris Franks: I’m Chris Franks. I’m Bill’s understudy. I have lived part time in Columbia County, in East Chatham, since 2008. And I am a very active and enthusiastic birder.

MF: I asked both of you to come and chat on this radio show, Beakuency, because there will be an event at the Columbia-Greene Community College Natural History Museum. We’re going to talk about that a little later, but first (to Bill Cook), I want to ask more about you personally. Could you talk a little bit about how your interest in birds started?

BC: When I first started teaching at Columbia-Greene, they offered some Saturday credit-free courses. As an employee there, I got to take them for free. I immediately signed up for several courses. I signed up for Mixology, how to make drinks. And I signed up for one with Rich Guthrie on bird watching. So, it was Rich Guthrie who got me started, and he’s been my mentor throughout my career, pretty much. I have to thank him for getting me started.

MF: Rich Guthrie, with whom people might be familiar from his appearances on WAMC, the birding show. And that's when?

BC: 1976, I guess, is when it first started for me.

MF: So it's not like you grew up watching birds?

BC: Oh, well, my early childhood experiences. My father was influential there. He taught me hunting, fishing, and trapping. I knew game birds, of course, because we shot them and ate them.

MF: You ate them?

BC: Yes.

MF: So you know how to dress them?

BC: Sure. Skin them and cook them. That's growing up in Columbia county in the 1950s.

MF: That skill probably helped you prepare birds for the ornithological collection?

BC: I suppose so. Growing up, I skinned muskrats and other things in my trapping experiences. So, skinning birds for the college museum, making study skins, came pretty easily to me.

MF: Wow. Very cool. So that’s how you started birding. And you have birded in all of the 62 counties in New York State. How did that happen?

BC: Oh, it was just a fun thing to do. I decided to — this was many years ago, decades ago, and I was very active in birding, and listing and that sort of thing — so I just, on weekends, I picked two counties that were adjacent to each other. I’d drive out western part of the state or northern part, or someplace else, and spend a weekend birding one or two counties on my own and just find a local motel to stay Friday night and Saturday night, and then drive home on Sunday. And had a good time doing that.

MF: This is pre-eBird app time. How would you get the information of where to go?

BC: Susan Drennan published a book, Where to Find Birds in New York State[: The Top 500 Sites] and I used that as a guide. It was published in the 80s.

MF: So you just looked at this book as a guide. And were they successful?

BC: Oh yeah. I had a Volkswagen Beetle and I drove all over the state and just had a good time.

MF: You also mentioned that you've already pretty much covered the whole states also, except for the three states.

BC: Most of the United States of America. Only three of the 50 states do I have left. That’s Oregon, Washington, and Nebraska. I plan to go to Nebraska this coming summer with my friend, Will Yandik. My daughter actually lives in Washington. So, I need to make a plan to go visit her in Washington at the same time.

MF: And you do the same, look up where to go ahead of time, although a state is much bigger than counties.

BC: It's easier now with eBird. I can just check the major hot spots on eBird, find out where the good places are. I’ve done that already for Washington and Oregon. So my destinations are already picked out. Make arrangements to go there sometime.

CF: She probably knows that when you visit you'll bird, right?

BC: Oh sure.

CF: It may not be good if your daughter says I'd like to come out and see you.

BC: Well, we'll have dinner together, things like that. [laughs]

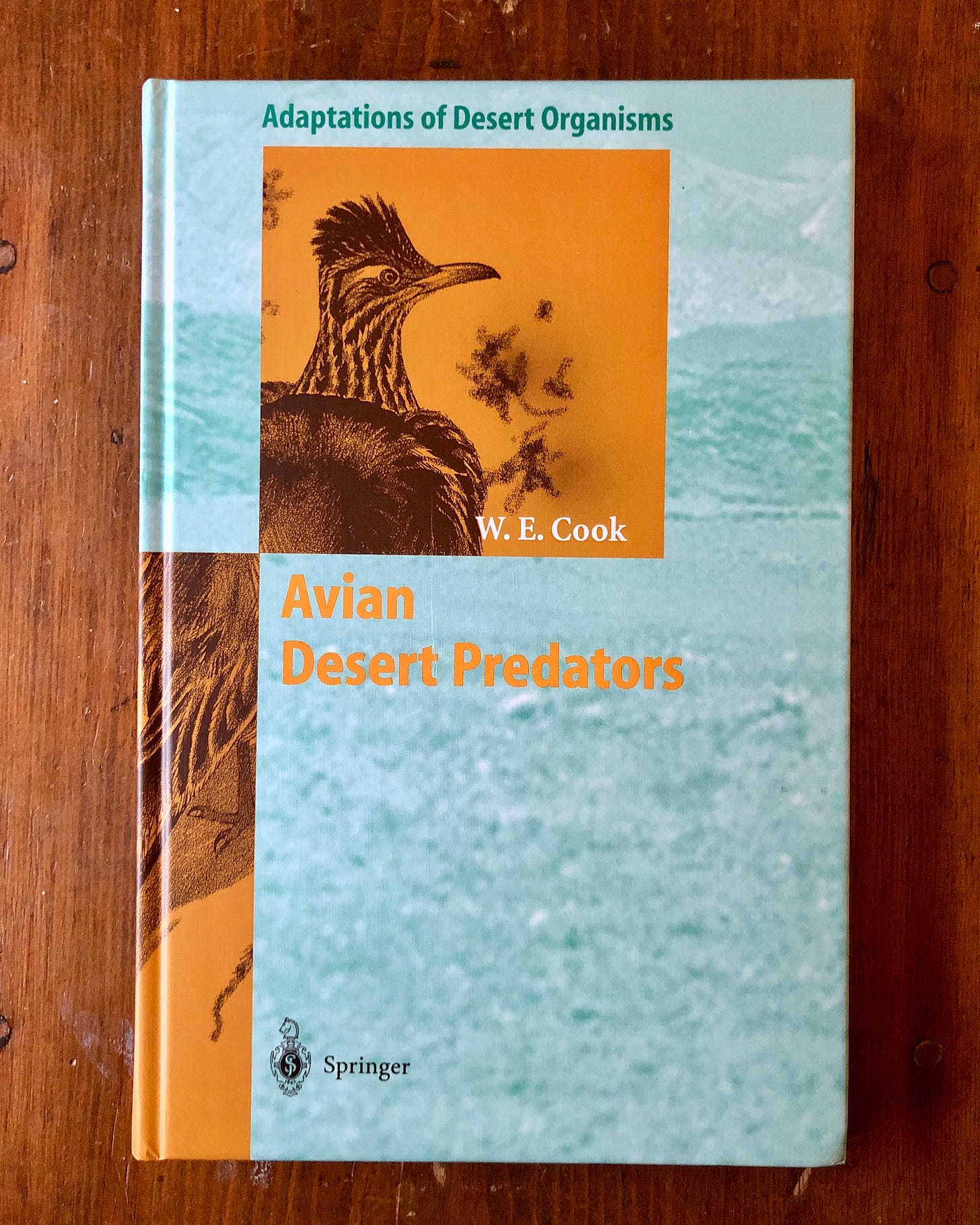

MF: [laughs] Why don't we talk about this book also — “Adaptations of Desert Organisms, Avian Desert Predators.”

BC: That was an interesting phenomenon in my life. I had never intended to write the book, but during my graduate studies, I wrote a paper about feeding relationships between birds and amphibians. I was taking an amphibian course at SUNY Albany with Margaret Stewart. I wrote a paper, a bibliography listing all the references that I could find for feeding relationships between amphibians and birds, birds that ate amphibians, amphibians eaten by birds, amphibians that eat birds, and birds eaten by amphibians. I made four lists and she said it was such a good job that I should publish it. So I did. It was published as a bulletin by the Smithsonian in Washington D.C.

And then, somebody by the name of John Cloudsley-Thompson, the editor of this series of desert adaptations. That book you're holding, one of the books that I wrote, is part of this series that he compiled of desert adaptations. John Cloudsley-Thompson, a British scientist, is a desert expert. So he encouraged several authors to contribute to his series. Publishing books about adaptations of birds or wildlife things to deserts, that was his specialty. So he asked me to contribute something about predator prey relationships in deserts. And I told him I was an ornithologist, so I restricted to the birds. So I wrote that book there, titled Adaptations in Desert Birds of Prey.

MF: It must include a lot of birds that we're not familiar with in Hudson Valley.

BC: Yes, African species and other desert specialists. My friend Will Yandik did contribute some pictures, some drawings and also a good friend, Jim Coe, living in Greene County, did some of the really nice artwork. He’s a really good bird artist. He contributed some of the pictures, like a comparison of a Lappet-faced vulture and an Egyptian vulture. Extremely nice comparison showing the different bill sizes, different adaptations for eating different kinds of meat of those two species of vultures. The Lappet-faced vulture has a huge bill. You can tear open the hide of a hippopotamus or elephant and get to inside. But the Egyptian vulture, very diminutive bill, they feed on the scraps and stuff that are left over at the end of the process.

MF: This illustration of the heavy beak of a Lappet-faced Vulture looks very different from the vultures we have in Hudson, also.

BC: Yeah, we have two species now here in Hudson. Originally we only had one, the Turkey vulture. Now a Black vulture has extended its range from the south into our area. So the black vulture is a common year round resident here in Hudson, Columbia County. The Turkey vulture is also changing its pattern. The Turkey vulture used to migrate out in the winter. Totally gone this time of year. But now we can find Turkey vultures here pretty much throughout the winter. Not very many, but a few linger around. So we have two species of vultures here flying around Hudson and the Greenport quarries.

MF: And this change happened pretty recently. This is during our lifetime.

BC: Oh, yes, within the last 10 or 20 years. When I first started birding back in the 70s, there were one or two reports of Black Vulture in Columbia County. Very, very rare accidental birds that kind of somehow got lost. But now they’re here regularly, extended their range into our area and beyond, further north. So, yes, they’re shifting their range north along with many other species of birds as well.

MF: It seems like this [winter, 2024] there are many Red-winged blackbird and we saw three Yellow-bellied sapsucker the other day, and these things [were] flagged when we reported on eBird… because they're not common this time of year?

BC: Yeah, the blackbirds, that’s similar to the Turkey Vulture, they are migratory, and they used to be pretty much absent in the winter, but now you can find Red-winged Blackbirds here throughout the winter commonly. The Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers, kind of a different story. They’re more of an altitudinal migrant. In the summertime, they go up into the Catskills or in the Berkshires. They’re hard to find here, down in the valley, but in the wintertime, they kind of drift down in the valley from the Berkshires. It was very interesting to me. One time, I did Christmas Bird Count over in Berkshire County with the Hoffmann Bird Club and I was surprised to learn that Yellow-bellied sapsucker is so common there, whereas it's less common down here in the Hudson Valley.

But I was also surprised that they had so very few or practically no [Eastern] Screech owls. Here in the Hudson Valley, we have Screech owls all year round. It's our most common owl. But over up in the hills, up in the mountains of Berkshire, they were almost unknown. That was surprising. That close and yet such a major difference in the bird population.

MF: There must have been a lot of changes over the years you’ve been observing birds.

BC: I've been birding since the 70s. There’s been a lot of changes, some increases and some decreases. We just talked about some of the increases like in the Black Vulture and the blackbirds. But some of the decreases are interesting and unfortunate. That includes ducks, waterfowl and also neo-tropical migrants like warblers. Both of those categories of birds have been decreasing dramatically.

Chris was talking about the Duck Count this past weekend and what you found. When we have four species or five Mallards, Mergansers, you were lucky to find some Goldeneye and Ring-neck Ducks. Well, 20, 30 years ago, we'd find maybe 15 species of waterfowl, including perhaps typically a raft of Canvasbacks. Thousands. You'd find a group of thousands of canvasbacks and if you're lucky and look through them real closely, you might find a Redhead. Goldeneyes were like a dime a dozen. All along the river you'd find big groups of Goldeneye. Now they're possibly a rare bird. And you’d find other things, Scaup and Scoters and Old Squaw which are now called Long-tailed ducks. Things like that would be relatively common on the river.

(Video: Common Goldeneyes swimming on Kinderhook Creek, Columbia county. February 4, 2025.)

MF: Is there any species that you stopped seeing or you see less now?

BC: Stopped? Well, let’s see. Loggerhead Shrike is pretty much all gone. There were a few around in the 70s. There are two kinds of shrikes. The northern one is called Northern shrike and the southern one is called Loggerhead shrike. We still get Northern shrike, as Mayuko knows, because she was instrumental in finding a really nice specimen this past month for the Christmas Bird Count. But the Northern shrikes only come down here in the wintertime.

In the summertime, we used to have a species called Loggerhead Shrike, but they’ve been gone for decades now. You can still find them commonly in Texas and still in the southern states, but I think they’re pretty much gone from New York State.

MF: I would also like to talk about the ornithological collection of Columbia-Greene Community College Natural History Museum. You are the curator. And the Alan Devoe Bird Club is going to have an event there. That’s why we also have Chris Franks, the organizer of the event, with us today. Would you talk about what’s happening, exactly?

BC: You want to answer that question, Chris?

CF: Well, why don’t I give the logistics first. And then we can talk about what to expect when they come because we've done this before. So the event is on February 10th [2024]. It's being held at the Columbia-Greene County Community College. There are going to be two sessions, one at 9 am and one at 11. And because it's interactive, not just an exhibit. So we'll get to that in a moment. So it's interactive participation by the people who come. There's a registration that you need to do. It is free, but you can email the Alan Devoe Bird Club and say you're interested in coming. Or you can also find us on Facebook under Alan Devoe Bird Club and send us a message there. And the website also has other information about the location and times and those things, which is Alan Devoe Bird Club www.alandevoebirdclub.org.

We held this a couple of years ago and it was very well attended and liked. So we looked for something to do field trip wise in the winter when travel might be difficult, it's 12 degrees out. And Bill has been nice enough to share part of the collection with us and birders. And again, it's open to the public. So I'll let him describe the collection, the size, how it came about and then some of the exhibits that we put out.

BC: Okay, thanks Chris. This program will highlight some of the special specimens we have in the collection and also maybe provide some fun opportunities possibly. Some of the exhibits include — well, we have an egg of Passenger Pigeon, an extinct species. So there’s something that’s of interest. We have some specimens in the collection that were collected in New York State. There are rarities from New York State. For example, Wood Stork, Purple Gallinule and Rufous Hummingbird are birds rarely found in New York State, but we have specimens that have been collected in New York.

We’ll highlight some of the other oddities, odd plumages. Like, we have some birds that are white; they’re not normally white. This is a phenomenon called leucism. It’s quite different. It’s a little different than what you would think of as an albino. A white bird that’s partially white, it’s called leucism, from the Greek meaning white. We have a white Red-tailed Hawk in the collection, a white Blue Jay. We have a chickadee with a white tail, things like that.

We also have some specimens of Cedar Waxwings that have red tail tips, rather than yellow tail tips. And there’s an interesting story about that. It took a while to figure out what that phenomenon was all about. It was thought that, at first, it might have been a genetic mutation. But it turns out that it’s due to their diet. Some Cedar Waxwings, when they’re young, they’ll eat things like honeysuckle berries, or something that has a red pigment in it. It’ll turn their tail band red rather than yellow.

So, we’ll highlight some of these interesting specimens from the museum, and then we’ll have a couple of interesting things for the people. A warbler quiz. A bunch of warblers will be out, so they can try to guess what species they are. They’ll have feeding adaptations exercises to play if they want to. So, that’s the idea, kind of fun. Field trip, indoor field trip, for the bird club

CF: It's also, I think, helpful, especially for birders or others in the general public that are interested. What purpose does having collections serve the scientific community and the rest? Because people usually now think about, oh, people in 1900 or 1860s went out with guns and just shot things, and you know, terrible. But there’s a scientific value, and you can see some of those things applied with the specimens and what they have in the collection.

And when scientists are doing research, they’ll go around to different places that have these collections to do measurements. Again, Bill kind of just mentioned it, but people were not sure if these were two different species of Cedar Waxwing until they looked at this collection and did the further work. So, there’s some scientific value, and I think it’s good to see how those things are applied and of interest.

BC: Yes, our collection has been used for many scientific research projects. One that comes to mind has to do with Red Crossbills. The species known as Red Crossbill is an unusual species, has an unusual breeding pattern, and they can breed any time of the year. Scientists now believe that these birds represent several different species. And so, studies have been done on them. It turns out we just, by coincidence, happen to have a very large Red Crossbill collection. Over nearly 50 specimens in our collection, collected by Robert Yunick, back when there was an eruption of Red Crossbills in the state. We have specimens of so called different subspecies. And one day, the researchers from New York City, from the American Museum of Natural History, came up. They wrapped up all my crossbills, put them in a box, and took them down to New York City, and they studied them for a couple years, and then sent them back. So, that was one way in which the collection has contributed to science.

We also have, perhaps our most significant bird in the collection is a Black-throated Blue Warbler that appears to be half male and half female. One side of the bird, the right side, has male plumage, then the left side of the bird has female plumage. So, the question is, what in the world causes that? That bird specimen was sent to the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. to do a genetic study. What they found is that both sides of the bird genetically were female. But, when I did the dissection, it did have a testis on the right side, and it did have an ovary on the left side. It had both kinds of gonads inside. But genetically, the whole bird was a female. The reason why it looked different was just apparently a hormonal variation. The testis produced male hormones for the right side, and the female ovary produced female hormones for the left side. And why both sex organs develop is a question.

CF: And Bill just mentioned something that I find very interesting. And he used this phrase which was “They used to”, or “we used to think”. In science, it’s not right or wrong; it’s based on the information and the data available at that time. This is what we — not me, I’m a layperson, just a birder — but Bill and the scientific community, “this is what we think”. And so then you go into the future, and some new discoveries and new things come up of evidence or information, and say, we used to think this, we now think that. And having the collections allows you to go back in time and see what the people were looking at and compare those.

And then the last one that I’ll give to you, because it just kind of ties into this: When people think of evolution, they think of it as being minute changes over long, long periods of time. But with Darwin, there were finches whose beaks varied based on the crop and food access that they had, and the size of the seeds that were coming. And so they found that evolution actually could happen much quicker to populations, not just over eons. And the way to determine those was actually to capture and measure these same, so to speak, species of finches, but with different attributes. Those are some of the things that come out of this collecting, or research and study.

BC: That was a fascinating study, referring to the Grants’ (Peter and Rosemary Grant, evolutionary biologists who studied Darwin’s finches) work in the Galapagos, showing that evolution is happening all the time. It goes back and forth. And it can be as rapid as one season. The size of the bills of a species of bird can change based on catastrophic events in just one season. The next generation of birds have larger beaks or smaller beaks based on the size of the seeds that are available based on weather conditions.

MF: I've heard that pigments in bird feathers, I think it was Blue Jay, that they don’t have blue pigments in the feathers.

BC: That is an interesting phenomenon. Yes, some colors are due to pigment. Like, the red in the cardinal is a red pigment. But the red of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird’s throat is not a pigment. If you turn the feather right, it just looks black. But if you change it, if you reflect the light through it just properly, then you get the ruby color. The feather actually acts like a prism. It sort of breaks apart the light spectrum and shines the red portion of the spectrum back to your eye. So, that is an interesting phenomenon. And apparently Blue Jays feathers are the same way. They’re not really blue, they just break up the light and send the blue light back to your eye.

MF: It's kind of mind blowing, but that's the kind of thing you have to look at the bird's skin to really know how that spectrum, the light and all that works.

BC: Yeah. So that's another reason why museum specimens are important for scientific study.

(The video below (not so well captured, but) shows the throat of Ruby-throated Hummingbird changing its color depending on the angle.)

MF: I was looking at the Columbia-Greene Community College Natural History Museum website and there was a search engine for your collection. And it’s got — let’s see — well, the sex of the bird, “Skull ossified”…

BC: Yes, skull ossification, that’s an indicator of the age of the bird. In the passerines — that’s the perching birds, or songbirds — the young birds, after they hatch, they have only one layer of bone in their skull. But sometime before the second year, a second layer develops, and the two layers are separated by little pillars that can appear as white dots on the surface of the skull. So, that’s one way to tell the age of a bird, you can tell if it’s a hatch-year bird or after hatch-year bird.

MF: And then there's some other more basic information like which country, which state, which county, township. And I saw there were a bunch of local, Columbia county collected birds.

BC: Yeah, I collect here mostly in Columbia County. The Columbia-Greene Community College does represent Columbia and Greene counties primarily. So, yes, the majority of our collection is local.

MF: And there's a “collector” and “donator”.

BC: Okay, what’s the difference between a collector and donator? Well, in the terms of the bird study skins, the collector is the person who stuffed the bird. The donator is the person who brought the dead bird into the museum, and the collector is the person who takes the bird skins, stuffs it, writes up a tag. And in my case, catalogs it in the computer database and that sort of thing. So, that’s the difference between a donator and a collector.

MF: The “cause of the death” was also interesting. There were a lot of roadkill, cat kill, window kill. The specimens came from many different situations.

BC: Yes, well, for our collection, I don't have a what's called a collector's permit. My friend Jeremy Kirchman at the State Museum, has a collector’s permit. He can legally go out and shoot birds for his collection. What I have is a salvage permit, which allows me to pick up dead birds. Believe it or not, it’s basically illegal for a common, everyday pedestrian to pick up a dead bird. Technically, it’s illegal. The reason for that is, if, say, a person shoots a Bald Eagle, which is highly illegal. And a police officer sees the person with the Bald Eagle, and the person says, “Oh, I didn’t shoot it, I just found it.” The police officer says, “Well, tough luck, buddy, you’re still under arrest because it’s illegal to have it.” So, that’s the reason for that law.

MF: That's what I was wondering. Because I think people find dead birds all the time — I guess window kill is very common.

BC: Yes, it is. Birds can’t see the glass, so they see the trees or something on the other side of the glass. They think they can fly through, and they fly into the window full speed and kill themselves.

MF: What's the oldest and newest addition to the collection?

BC: Okay, well, the oldest one we have is from 1873, I think it is. That was a Solitary Sandpiper. But what's interesting are old specimens. We have several, half a dozen or so from Eugene Bicknell, who has specimens from 1879 to 1881, stuffed by Eugene Bicknell.

MF: Bicknell, isn’t it in the bird name?

BC: Yeah. He is honored in the name of Bicknell's thrush, which breeds up in the higher elevations of the Catskills. He was also somewhat of a botanist. There are, like, seven plant specimens named for him as well. But he was somewhat local. He was born and lived most of his life in New York. He died in Long Island. He was born in the Hudson Valley somewhere. He did work as a banker in Paris, I know, for a while. But he was interested in natural history, and did both ornithological work and botanical work. He wrote some papers about birds of the Catskills in the Hudson River Valley. So, Bicknell is relatively a well known name in the bird world. And we have some of the specimens that he stuffed in our collection. Those are older specimens in the late 1800s.

In terms of newest specimens, still collecting all the time, a week or so ago was from my friend Will Yandik; he gave me a Savannah Sparrow that he collected in December. That’d be the newest specimen.

MF: So those are the things that people can expect to see when they come to the event.

There was another thing about certain bird skins that you have in the collection, which was prepared by the “Feather Thief”. There was a nonfiction book titled “The Feather Thief” that came out in 2019. It is a story about this 20 year old American guy who broke into the British Museum of Natural History which had one of the largest ornithological collections in the world. He wanted those rare bird skins in the museum because he was obsessed with fly tying for fishing, and apparently — I didn’t know any of this, but — fly fishing’s got many esoteric recipes that use rare bird feathers. And so, that crime became a big story. And speaking of local bird people in the Hudson Valley, I heard that he’s local.

BC: Can we mention his name or not?

MF: I think it’s okay.

BC: Edwin Rist; He was a student of mine in 2003. He took my bird course. He was an excellent, excellent student. Very intelligent, very diligent in his work, very dedicated in whatever he did. And he took my bird course. And, in the process, we do have a specimen in the collection that he prepared. He prepared a skin of a Barred Owl. So, we have that with his name on it.

But what he did at the Natural History Museum at Tring was so incredibly unfortunate. Some of the birds were recovered, but he stole birds of paradise. He stole Cotingas from South America. Some of them were collected by Alfred Russel Wallace. I don’t know if you know who he is, but he’s like Darwin. He came up with the theory of evolution, and he was a colleague of Darwin’s and deserves the same amount of credit that Darwin has for coming up with the theory of evolution by natural selection. Anyway, some of Wallace’s birds of paradise from New Guinea, Edwin took, which is really unfortunate.

The good thing is that he still grew up to be a fine young man and he has a good career as a flute player in Germany. And so, he still is making a contribution to life and science. But he did a bad thing in his life, and everybody in his family and friends are unhappy about it. And it was a tragic event in terms of natural history collections.

MF: Is he also from Claverack?

BC: Yeah, he and his family lived in Claverack. Yep, my hometown. [laughs]

MF: [laughs] So that's another thing that people can expect to see.

CF: Let me just make a happy note. When I first started birding in Columbia County and joined the Alan Devoe Bird Club. One of our active trips each year, we do one in the spring and one in the fall, is at Olana Historic Site. And Bill traditionally has led that walk. There’s one on Labor Day and one in spring. And what was so much fun for all the members of the club was Bill, while he was teaching, would suggest to some of his students that if you would like extra credit, come on the walk. And so, one, that’s funny because it’s 7:30 in the morning on a Saturday and getting a college student to get up. I used to say to them that they must really need the extra credit to get up early on a Saturday. But they would come, and they were interested in asking questions. Oftentimes, they were not properly dressed for the weather, which also was kind of amusing. But it really was a nice interaction between experienced birders that go out all the time, and this young group that is studying birds and then not just in the classroom, but coming out into the field. Everyone looked forward to those walks when some of Bill’s students were likely to come. It was always very enjoyable and fun.

MF: But you didn't have a chance to meet that celebrity of ours, the local celebrity?

CF: No. But maybe other celebrities of the birding community would show up. Since Bill also mentioned Mr. Guthrie — one of my first walks with the club was with Bill, and we were doing the Hudson River South. There’s a sister club of ours, the Hudson Mohawk Bird Club, and they would do a walk called the Hudson River North. And we were, 10 or 12 birders looking through our binoculars, trying to hear. And then we heard this Great Horned Owl call. We were all pretty excited to hear this, and looking through our binoculars. But Bill is not only a great birder through binoculars, but his ears are great, too. And he goes, wait a minute. And it was Rich Guthrie down the road doing the call, knowing that we were on the walk. So, I had to take my pencil and erase my listing of a Great Horned Owl that morning. Bill was able to say, no, I’ve heard that before.

BC: Yeah, I've worked with Rich Guthrie enough to know his imitation of Great Horn Owl. [laughs]

MF: [laughs] That's really funny. Yeah, we did a pretty successful walk that’s led by you, Bill, at Olana this year too. That was a very productive walk.

BC: I have to thank you for picking out the good birds. As I'm getting older, my eyes aren't quite as sharp as they used to be. So I was depending upon folks like you, Mayuko, to see the birds and point them out to me so I could identify them. So that's what made it so successful. The people on the trip walk were very helpful in terms of finding the birds and pointing them out.

MF: I feel like my role in the group is like a dog. Just bark at something and people can tell me what it is. [laughs]

BC: That’s an important role.

MF: Listeners can find the information on those walks organized by Alan Devoe Bird Club also on the same website at www.alandevoebirdclub.org.

Thank you so much for all this wonderful conversation.

BC: You're very welcome. Thank you for inviting me. It was a pleasure being here.

Bird-inspired Music of the Month

The live broadcast of this episode on WGXC featured Compositions Ornithologiques, a 1996 release by Bernard Fort, a French composer and ornithologist. https://electrocd.com/en/artiste/fort_be/albums