Beakuency welcomes Will Yandik, a fourth-generation farmer at Green Acres Farm in Livingston, Columbia County, with a background in environmental science. He is exploring practical ways for farmers to create ecological benefits without sacrificing too much of their already challenging work. The project we will hear about today, which he has been working on for four winters, examines how farmers can plant certain cover crops to not only combat climate change, but also create a habitat where sparrows can find food and shelter from the cold.

Many of us struggle with not knowing what to trust and the fear of uncertainty. Will's insights tell us how we, as consumers, can make choices that support our local farmers and wildlife, and build trust in our community. He shares how his training as a scientist to always consider statistical probabilities and leave room for other possibilities, and his experience as a farmer observing the resilience of birds year after year, have given him the strength to live with uncertainty.

Research: Cover crop as habitat for winter birds by Will Yandik (Hudson Valley Farm Hub)

https://hvfarmhub.org/will-yandik/

Green Acres Farm

http://www.greenacreshudson.com/

This interview was recorded on February 5th, 2025, and broadcasted on Wave Farm’s WGXC 90.7FM on February 22nd, 2025.

Interview Transcript

Mayuko Fujino: Could you briefly introduce yourself?

Will Yandik: My name is Will Yandik, and I am a farmer in Columbia county in the town of Livingston. My family and I own Green Acres Farm, which is a mixed farm of fruits and vegetables that we've owned since 1915. And when I'm not farming, I am studying birds. I'm an ecologist by training. My background is in environmental studies and science at Princeton and Brown University, and I work as a freelance ecologist.

MF: And this project that we're going to talk about today is part of your job as a freelance ecologist [and] researcher.

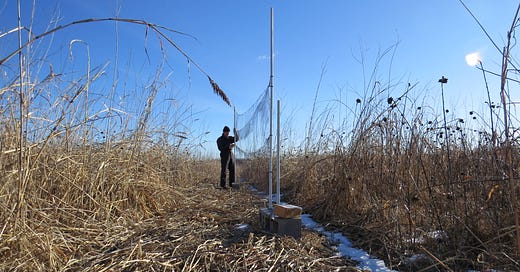

WY: That's right. We're here at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub in Hurley, New York, in Ulster county, where I've worked for four winters examining how farmers can plant certain crops and leave them standing in the winter. They're called cover crops, which farmers plant for a variety of reasons, either to fight weeds or *sequester carbon or improve soil quality.

*Carbon sequestration is the process of capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂.). (usgs.gov)

And I'm interested to see if any of these cover crops could do double duty doing the work that they do for farms, but also providing additional habitat opportunities for birds. New York State is a national leader in recognizing that the agricultural sector has a lot of opportunity to help in the fight against climate change, particularly in its management of soils. Soils sequester a significant amount of carbon. And there is money available through county soil and water offices and through other state and federal programs to help farmers pay for the costs of seeds for planting cover crops and to diversify them to add additional species or at other times of the year that they might not afford or be able to afford to do so.

And I think it's a great opportunity, as farmers in general in our area in the Hudson Valley are interested and being subsidized to plant more cover crops. I'm more interested in having some ecological voices added to that to say, hmm, this is something that we can plant, that we know sequesters carbon. What is its value in terms of providing habitat for birds?

MF: I read your report about this whole project that we're going to ask you more about, and because I'm coming from a bird fan point of view, I'm reading it only from [that perspective to think that] this is a great thing to do for birds. But it's actually good for us, too.

WY: That's right. The common thread through all of the research questions that I've recently been asking are the recommendations that we as ecologists making, are they feasible? What is the likelihood that an average farmer will be able to adopt those recommendations within the normal operations of their farm? And that's a really important question because there may be lots of things that farmers can do that are amazing for birds.

I would love to see a farmer someday flood their field so he could finally have a good place to see shorebirds in the Hudson Valley. [laughs] But that is not a good thing for the farmer's bottom line. What's different about the question that I'm examining at this present moment is that these are already operating within the normal model that a farmer would adopt to do things that are good for that farmer, independent of any consideration for wildlife. So that's a powerful starting point. If farmers are doing something, the question is, how do we tweak it? What are the small, easy management differences that we can recommend that might have very big impacts on birds? And I find that that's a great conversation starter to engage with farmers who are not typically thinking about how to provide wildlife habitat at all.

What's interesting about the project that I'm doing now, it is a winter study. So there's not a lot going on on most farms. And the cover crop that I'm studying is a mix that's dominated by a grass called Sorghum Sudangrass. And typically, farmers who plant it mow it out in the fall. Just as a task to get off the chore list. What I'm examining is whether if farmers simply mow it in March instead of October, leaving this cover crop through the winter, does it have the potential to provide quality habitat for sparrows?

MF: Does the timing matter, when you mow?

WY: Timing is critical for a variety of on farm tasks because birds have predictable and regular cycles for breeding and roosting and wintering. And so again, the cover crop that I'm describing, it grows about three feet tall throughout the summer. It's a warm season grass. It's planted in typically June or July. It grows thick and provides a quality, dense habitat through the spring and summer months. And farmers, as I've mentioned, typically mow it out in the fall, by convention. There's no penalty for most farmers for leaving it throughout the winter months. And so what we're trying to do is convince farmers to leave it through the winter months, where it provides a kind of temporary winter habitat. And then farmers can go back to their field in March or April, where many of these winter sparrows have already departed to their breeding grounds, and mow it with minimal consequences to those winter sparrows.

So the timing is everything. If a farmer mows this cover crop in October, then the bare stubble that would result and remain through the winter provides very little windbreak and provides almost no seed or food source for birds. So the timing here is critical.

MF: It also doesn't harm farmers’ business in any way.

WY: That's right, because they're not using those fields during the winter months anyway. So this is like a great introductory project for farmers making a small ask that might have a big impact.

MF: You have a few target species. Would you talk about what kind of sparrows are we talking about here?

WY: Sure. We're looking at three species of sparrows, one of statewide concern, a species that's declining, the Savannah sparrow. Savannah sparrows, like all grassland breeding birds, are declining rapidly across their entire breeding ranges in North America, almost entirely due to habitat loss. So Savannah sparrows, which were once extremely common on American farms when farming constituted 60, 70% of the landscape, have now been reduced by double digits simply because they don't have as many places to live and breed. So I'm interested in studying the Savannah sparrows because they're declining and we're concerned about that.

I'm also looking at Song sparrows, which is a resident, a year round resident here in Ulster County. 100 years ago, we wouldn't see as many Song sparrows in December, January and February. Now, with a warming climate, many Song sparrows don't even leave our area. They reside here 12 months of the year. I wanted to look at Song sparrows because we clearly know from the ornithological literature that birds that nest near their wintering locations often have first crack at some of the best breeding sites. So we're studying the Song sparrow here in Hurley to see if we provide this winter habitat. Do any of those Song sparrows that use that winter habitat remain and breed earlier than some of the other Song sparrows that might be arriving later in the spring?

And the last sparrow is a winter visitor and that is the American tree sparrow. They breed up in the Canadian taiga and wetland areas and this is their winter vacation. They're here during the winter months because it's a warmer area with less of a severe climate. And we're looking to see how often those birds remain in places like this year after year.

MF: I'm here today to check [out] how you actually do it in the field. And I saw you putting up the net and we did catch two birds today.

WY: We did catch a Song sparrow and an American tree sparrow. I find that wind makes for poor banding days. There's a little bit of a wind today. And what the wind does is it blows the shelves of the net out making it more visible. The whole way that a mist net works is that the bird typically will fly through and doesn't see the net. It bounces into the net and then is caught into one of the pouches of the net. I tend not to put too many nets out in the winter. Winter banding can be tricky because there are some thermal regulatory challenges on the bird and we don't want them to sit in the nets too long.

But we did get two birds today. And a typical procedure for gathering information from that bird is we take the bird out of the net, we put it in a banding bag, we weigh it, we look at the amount of fat that the bird has, and that's a simple check of that, is to take the bird in your hand gently and to blow. And what's considered the wishbone or furcula region, there's a depression in the chest of the bird that will, predictably, in patterns, gather fat as the bird accretes fat. And there's a scoring number from 0 to 6 or 7 that assesses the amount of fat on that bird.

Some of the birds today, both of the ones that we caught, we’re also taking some fecal samples. So we place the bird in a bag which has a screened bottom, and we collect those samples, which will be frozen and sent to a lab in Colorado which does DNA sampling. Most amazing thing, in my lifetime, I'm 47 years old, even in my relatively short career, the cost of DNA analysis has gone down so dramatically. I mean, to do these kinds of DNA analyses for a small independent researcher like myself would have been impossible 25 years ago. And it is absolutely routine now. You can actually take DNA samples from your pet. If you wanted to know what your dog or cat was eating, there are labs that are marketing for that. [laughs]

But these samples will be sent to Colorado and in a few months, it will give me a genetic profile of the seeds that the bird was eating. There are some positives and negatives. With DNA analysis, it's sometimes not very good at detecting items in the bird's diet that are very low. But if anything shows up positively, that's usually a very strong indication that the bird has been feeding on it regularly and recently because that DNA doesn't last very long in the animal's gut, in terms of sparrows. That does vary by organism. But for sparrows, if we see certain profiles for seeds or plants, we have a pretty good idea and understanding that it's been eating those recently.

MF: I see. Who are these people In Colorado?

WY: An independent lab that contracts with lots. I'm also collaborating with Conrad Vispo, who is looking at the inner contents of various insects. So we're pooling our samples to save costs. Conrad is a member of the Applied Farmscape Ecological Research Collaborative, along with myself and several other researchers that are working here at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub. So we pool resources and share resources.

MF: I'm trying to picture how you send these poop.

WY: Oh, they're in small plastic vials. At the end of today, they'll go home and they'll be put in my freezer. And at the end of the season, they all get put in a special envelope and they're shipped, they're overnighted out to Denver.

MF: I see. So not like USPS regular mail.

WY: Yeah, but there are certain what are called primers, which are chemical stabilizers that you can mix that will extend the time in which a sample like this could be in the mail without the DNA degrading. DNA is pretty stable if you put it in the right conditions. Every once in a while the permafrost will recede and the Russian steps and we'll find some woolly mammoth remain and some smart scientist will take a piece of the fur or skin and manage to get a viable piece of that DNA. So it's amazing how DNA can be durable in the right conditions.

MF: You mentioned the fat levels [of sparrows] and it indicates certain things. Would you talk about that?

WY: Yes, that's an interesting question. So when we're talking about ground feeding sparrows, many researchers, dozens of researchers have worked out that against common sense, in many cases, birds with little fat reserves are healthier than those with a lot of fat. And the reason for that is that in ground feeding sparrows, at least not all organisms and not all birds, but in ground feeding sparrows, typically the fat that they accrete is in response to the predictability of their food resource.

Now, what do I mean by that? So when sparrows are in an environment where there's a lot of periodic snow cover, for example, or there's a lot of predator harassment where they're not able to feed for very long hours during the morning, those are the birds that we see with very high levels of fat, because fat is essentially an insurance policy against starvation.

So when your food resources are unpredictable, the birds physiologically add more fat as an insurance policy for the times when food is not readily available. All of the birds that we're seeing in this habitat, this cover crop, dominated by the Sorghum Sudan, and Sorghum Sudan makes a fat seed that looks like the kind of red millet that you see in some cheap bird feed mixes.

Except unlike the millet, it's a very nutritious, high protein seed that's 17% protein. And as you can see walking around this habitat, the seeds are everywhere. So the birds have readily daily access to this protein source every day. And as such, that predictability of their food leads to a physiological response in that those birds have very little fat.

They don't add the fat to their bodies because they don't need that insurance policy. They're living fast and loose because the food is there day in and day out. The regularity at which they feed sends a hormonal response in a complex hormone environment in their body. Birds respond to hormones that govern so much of their lives, from their breeding cycles to their urge to migrate to the amount of fat that they sequester on their bodies. And part of my study is I did compare the fat levels of birds found in the cover crop that I'm studying versus those found in less managed habitats, like Song sparrows found in Livingston along a weedy beaver meadow that had been abandoned and hedgerows that we've been looking at throughout the Hudson Valley. And those birds show a lot more range of fat levels and on average have more fat than the birds found in this cover crop, which is really like a giant bird feeder. It's just a field that's like a giant bird feeder. And you can see, you can measure the amount of seeds in the birds will reduce that seed load if measured from the 1st of December until the end of February. It's astounding. In some of the most dense patches of Sorghum Sudangrass, there can be 3 to 4,000 seeds per square meter. And the birds eat, in some cases, 60 to 70% of those seeds by the end of the year.

MF: So even then, still some leftover.

WY: There are some leftover. And that's the snag in this, in the recommendations to farmers, because if you are planting corn after this Sorghum Sudangrass, the sprouting corn seeds look an awful lot like the residual seeds that will sprout from last year's Sorghum Sudan crop. So in part of our recommendations, we're partnering with farmers and trying to understand this may be a great low cost option for farmers, but there are some caveats, meaning that some of the residual seeds from Sorghum Sudangrass may compete with corn specifically. And the fact that the seed sprouting seeds look so similar may make it harder for farmers to cultivate the corn because it's difficult to distinguish between the corn and the sprouting Sorghum Sudan seed.

Other crops like fall squash and pumpkins and tomatoes don't have that problem. So we plan to write a final report at the end of the season, and some of those nuances will be in those recommendations.

MF: You're making comparisons at different sites. So you go there and do the banding, or you work with somebody?

WY: I have been doing all the banding. I have had a few volunteers that have been helping me. And there's Teresa Dorado, who works here at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub. She's been helping me band this season. The population sizes that I'm studying are not overwhelming. So, you know, the population side of song sparrows at this site may be 50 to 60 birds, which sounds like a lot, but you never catch 50 or 60 birds in a day. And some of these other comparison sites have populations, I estimate, of 10 to 12 song sparrows. So I have been able to manage by myself. It's been a busy four years in the winter.

MF: Yeah, because you have to travel [to] all those locations.

WY: It has been a lot of travel.

MF: I mean, the Green Acres farm, that's where you are.

WY: That’s easy. Three bounds outside the back porch and I'm in the field.

MF: Right. But where's the Beaver meadow?

WY: That is a site also in Livingston, a few miles from our farm.

MF: Okay, so that's not too hard. This [Hudson Valley Farm Hub] is the farthest.

WY: This is the far one in Hurley. It takes about 45 minutes to get here from my home in Columbia County.

MF: The graph on the report was from 2021 to 2022. That's when the project started?

WY: I started in 21, that's right.

MF: Have you noticed any significant difference since? Because there's been some crazy weather, like drought last year. All those things would be a factor?

WY: One of my study years., the Sorghum-Sudan warm season cover crop planted by the farmers here at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub did not produce enough biomass to study. So that year we sort of shifted gears and we were looking at sparrows in other edge habitats and looking at specifically how the American tree sparrows had returned to this farm. But that was almost a lost year. And that's farming. There's good years and there's bad years. And birds can deal with that. Birds have evolved over millions of years to take advantage of patch dynamics in the landscape. If they would return to a wintering location year after year, and the prey species or target food source there is low, they are smart enough to move somewhere else and find it somewhere else. So I don't believe there was a negative impact on the birds, but there was just a negative impact on my study where I didn't have data for one year.

MF: But the overall trend you've observed over the course of what, almost four years, stays the same?

WY: Yes, with some qualifications. So one sub question within the study is the Sorghum Sudan has two cultivars, meaning farmers can purchase two different types of seed. One is a sterile variety that does not produce the seeds that these birds feed on. And the other is the non sterile, produces heavy seeds. So one of the questions we were trying to assess early on in seeing birds in these habitats, are the birds attracted to these cover crop areas because they are good windbreaks and they're feeding on the residual weed seeds that are found everywhere on farms? There's no farm that doesn't have at least a few weed seeds here and there. Or really is it the food resource, the seed head of the Sorghum Sudangrass, that's attracting birds? And what we found is that the habitat value is not zero if there are no seeds present. We still find sparrows in them, but we find far fewer.

So when we plant the non sterile variety that produces viable seeds, we see almost an order of magnitude more sparrows, ten times more sparrows. And that fat signature that we talked about is stronger in years where the seeds are present. So the birds have far less fat in years where they're abundant seeds than when they're not.

But again, I can't stress enough that the habitat value is still better than a bare, you know, a field that had not been planted to cover crops at all. So it is still an alternative, valuable habitat environment for a variety of sparrows, even if they're not feeding on as many seeds or not. So that's something that we could tell farmers that are planning to plant corn after Sorghum Sudan and warm season cover crops. You can plant the sterile variety, you still get the thick biomass which is sequestering carbon, but you're not getting all the seeds that may persist as a potential weed source for your next crop.

MF: So that's less of a headache… in theory, because we just walked by [the field] and you mentioned that there was a cross pollinating… or what was the word you said?

WY: Yes. So the stand that we walked through today is actually the sterile variety. But there was just enough pollen from a mile away that blew in. Where there are a few seeds and there's that small amount, there is still enough to attract a lot of sparrows.

MF: Yeah, there were a lot of activities.

WY: Really an incredible structure. The Sorghum Sudangrass, even though it's not a native grass, is a kind of analog of a cattail marsh. If you've driven by or walk through a cattail marsh and you see how all the stems bend over, the term is called lodging. And it's all those bent over stems that form dozens of little tunnels and tents that these sparrows get under. This winter we were very surprised to find a LeConte's sparrow in this study location. It was only the second or third LeConte's sparrow sighting for all of Ulster County. And this bird was incredible. I found it while doing research on the day was this circle's Christmas Bird Count day. So it got included on the Christmas Bird Count.

MF: Good for them!

WY: I was pretty sure what it was because I got close to it, but I was not able to get a photograph of it. A team came back to try to relocate the bird an hour later. This bird, I mean, when I say you almost could step on this LeConte's sparrow before it flushed. I've never seen such a skulker. And it's able to do that because this cover crop, again, forms these very, very dense thickets. And those thickets are available as a windbreak for birds, whether they're feeding on seeds or not. I always say, you know, a bird's calories are like a bank account. It doesn't matter whether, I mean, a calorie saved is just as good as a calorie eaten. So a bird that can save its energy by staying out of the wind is in just as good shape as a bird that goes out and eats an additional calorie to stay warm. And you can see today where there's a five to six mile an hour breeze blowing through the Esopus Creek Valley here, the bird activity is greatly reduced. The birds are there, we can hear them. We can hear the location calls. We're catching a few in the nets.

MF: There were even some singing.

WY: Yes, and there are a few early intrepid Song sparrow singing today. But if you came back here at dawn, perfectly calm, you would see dozens of sparrows. It's amazing how they hide. Really, it's incredible.

MF: So this report I read, your report on the Hudson Valley Farm Hub website. I'm going to read this part for the listeners who haven't read it. In your report you said:

My challenge to our community is as follows: If you are a farmer, can you think of ways to tweak management to leave a bit more room for wildlife? If you are an ecologist, can you ask questions that relate to organisms inhabiting the practical world of humans? If you are a consumer, can you dig past easy labels such as ‘organic’ or ‘sustainable’ to understand (and reward) farms of all backgrounds who make room for wildness?

And I think most of the listeners, including myself, are neither farmers or ecologists. Most of us are consumers. And so I wanted to ask you if you had any suggestions for us as consumers, any good ways to learn more about farms of all backgrounds: why farmers make the decisions that they make and what can we do to support them, where can we go to understand them better?

WY: Those are great questions and I think the most important takeaway from that quote is a sense that we're all in this together, that if we're interested in protecting habitat for birds, it doesn't matter whether you own property or not. You have tremendous power as a consumer and the things that you choose to buy in reshaping your local and global communities.

And so there are some labels that are really excellent. For example, there are incredible, well regarded, internationally recognized and verified labels for things like shade grown coffee. For the local level, it's trickier because those standards are not vetted at the scale of our community, local community. And what I say to folks is there's no shortcut, there's no simple label or certifying third party agency that will ever take the place of chatting with your farmer at your local farmer's market, farm stand, or even digging deeper on the labels when you see something offered at your local grocery store.

The key is to understand that farmers are stressed. They are operating in really low profit, low margin businesses and many are going under. So when I tell people to talk to your farmer, it's important to go to your farmer and learn, in a non judgmental way, what their philosophies are and what their growing practices are.

You don't come to a farmer armed with some article that you read in a national publication demanding them to grow something this way or that way because you just don't know enough about that farmer and their situation. But I find that those individuals that take the time to know their farmers with a sense of shared mission, with a sense of humility, neighbor to neighbor, get a lot of information and build something much bigger than a greater understanding of what you're buying. You're building trust in your community. Not every farmer can grow organically. But you might be surprised. That farmer, maybe that farmer's a hunter or likes to hike and has noticed nature on their farm and strike up a conversation about where there are turkeys or where they might have seen a woodcock.

And it goes from there. I can't stress that enough. The tone at which you approach a farmer really matters. You can ask about their growing practices. You know, ask which crops, instead of simply asking are you an organic farmer or not. Maybe a better suggestion might be to see if the farmer has certain crops that are available that are sprayed less and just say, would you be able to steer me towards some of the things that you're offering that are sprayed less than others? And that would be how I would handle things at my own farm and my own farm stand. For those that know a little bit about farming in the Hudson Valley, you know that tree fruit, particularly apples, is one of the hardest things to grow organically. But some things, like apricots and other plums and stone fruits, are much easier. And when people come to me on my farm stand in that humble but friendly way, I think everybody wins because I can steer the customer towards something which genuinely does use fewer pesticides. And we've created a situation of mutual trust. And maybe we could build on that relationship over time.

The other way I would answer or add to this conversation is that in the ecological world, this is an area, a growing area of my interest in my research. Rather than making the dichotomy of growing organic versus non organic, we're starting to look more closely at intensity. What do I mean by that? So it's possible to be a certified organic farm that does not use any non organic pesticides or herbicides, but that farm might cultivate every square inch of their property from property line to property line, with almost no habitat whatsoever.

It's also possible that a farm can be conventional, spray apples in a conventional manner, but they might have 30 or 40 acres of woodlot or marsh or some other habitat on their farm that has very, an appropriate buffer where those pesticides are not reaching. And the biodiversity of that farm could be 100 times the organic farm.

What we're looking at is the intensity of that farming. And we're finding in the ecological community that the intensity of farming is at least as important as whether or not that farm uses chemicals or not. And so with this study, with future studies, I'm really interested in finding ways to provide a footprint for wildlife on farms of all backgrounds, whether they're organic or conventional.

MF: People wanting to have these easy labels, I think, comes from fear. To deal with complexity, and not having a straight one right answer, and instead being told that, “well, it could be this or it could be that, in this situation, it could be this,” that's a lot to deal with and leaves lots of room for unknown. It's a primal fear, not knowing what's going to happen. And a lot of people, I think, cope with [it by] just jumping onto what's right and what's wrong. And almost fanatic about [it], like we were talking about the labeling around organic products being almost like a germaphobic obsession with this cleanliness and being right. And I think that's really a coping mechanism with this fear.

And I wondered how you… especially farming — I mean, life in general is just uncertain — but farming, you deal with lots of different factors. How do you find your strengths to cope with this? Are you afraid, or you found a way to cope with it? How does it work for you?

WY: That's a great question. There's a lot there to unpack. I think you're right, and by no means am I anti-organic. I think that's a great compass point. But you're correct. I think some people take it to a kind of religious fanaticism out of cultural superiority, without really understanding what it takes to grow something organically.

Particularly in the Northeast, where we have very strong fungal pressure from our pests because we're in such a humid climate. It's good to be considering the things that you're buying rather than responding to price alone and to think about how it's produced. But we do need some flexibility, and that's a common problem that scientists face, whether we're talking about birds or organic produce or anything.

Science is a discipline of rigorously investigating unknowns. It is not a religion. It will never, in science, we never say that's 100% right. We talk about statistical probabilities and we say, boy, 95 times out of 100, that's likely to be the pattern. And I think that difference in language between the way scientists talk in terms of probability and relative certainty versus the rest of the world, that looks, “hey, you guys are the scientists wearing the white lab coats. Tell us what the answer is.” And sometimes science can't do that. It can do it better than most other forms of inquiry, like reading tea leaves or sticking your finger in the wind and guessing. But it's not perfect. And I think it takes some humility on the part of scientists who are trained that since their earliest moments of their career, that evidence points us in directions, sometimes strongly, but never entirely.

Scientists get that as a part of their rigorous training. The public, I think, struggles with that uncertainty. But that's just the rules of the universe that we live in. We must deal with uncertainty at all times. And scientists, no matter how certain they are of something, always leave the door open to crack, just in case some radically compelling new evidence comes that revolutionizes the way we think about things. That happens. That happens in science. It happened when we discovered DNA. In geology, it happened when we discovered plate tectonics. Oh, my god, the world is floating on these big, giant slabs of rock that are not stable, but they're moving violently and rubbing up against each other. That was radically, radically changing for geologists 150 years ago.

So go back to the basics. In terms of understanding your food supply, the best thing you could do is grow your own food. You know, if you have a piece of ground, many of your listeners might own property here in the Hudson Valley. Think about how you can make room for wildlife on your own property. Try your hand at growing some organic food. It really gives you a sense of appreciation when you go outside and 90% of your crop was ruined by some bug or fungus.

MF: So what you're saying is kind of like when this fear for unknown is abstract, when it's something that you just read on the label, and you don't know the entirety of it, you don't have the firsthand experience, then that's actually maybe more scary. And when you get to know it in your own life, that uncertainty sort of becomes part of your life, and maybe that's less scary.

WY: That's right. And again, it gets back to trust. The best thing that you can do is buy your food locally. I mean, if I buy from some national brand, every aspect, from the color of the packaging has been created by a team designed to sell that. And so there's information that's being promoted that might be questionable, and there's information that might be suspect that's being suppressed, I have no way of breaking that wall down against Nabisco or any of these national brands. I don't want to pick on Nabisco, but any national brand, I have no chance as an individual consumer of peeling back the layers of that onion. But if I go to my local farmer's market or farm stand or talk to a grower in my community, even if you don't like the answers, you're going to be getting reliable information and then you just make a choice as a consumer. But I would bet that as most farmers deal with direct consumers, they notice that happy customers buy more things. And so it's a two way street. It's in the best interest of farms to provide the most transparent understanding of their growing practices to simply develop good customers and sell more. Everybody wins.

MF: I guess familiarity would be a good coping method because I was just thinking about [the time] when I moved to the United States. It was frightening even just to go into a deli just because I don't know how it works.

WY: Can I tell you, that is my experience in Japan. I don't read kanji and everything I could not read. I'm just, it's like literally throwing a dart, like what am I gonna get? Am I gonna get fish or some deep fried snail thing or something that I've never even heard of? Let's just roll the wheel. It was very alarming.

MF: Yeah, it's terrifying. I remember it being so terrifying and I wondered about it at the time. But just being familiar lessens that fear and eventually you become comfortable with just going into a deli. So I mean, same thing could be applied to any sort of fear for uncertainty.

But have you been always kind of comfortable sitting in this very uncomfortable place of not knowing since you were a younger person, maybe being born in a farmer family?

WY: Yeah. So to answer the second part of your question about a farmer that deals with uncertainty, I've grown up around it and there are good years and bad years. My father died with $5 in his pocket. My father died at a time when the farm was not doing well. So those were, you know, indelible marks on my childhood. It's risky and I think you just have to be comfortable with that level of risk as a farmer. You are gambling every year. Climate change is empirically making it harder as our climate extremes start to creep into even safe mid latitudes like the Hudson Valley.

And there's hope in it. After all of this, all of my life experiences, I am at my core an optimistic person because of the observations that I make in nature. Nature is incredibly resilient. Birds are incredibly resilient. They're survivors. They're able to live and reproduce and persist after human beings have radically, radically altered their environment in North America, and many of them are still here. And it's a call to action for those of us that continue to look at the natural world around us, to see and to derive benefit from that hope.

We know that when we eliminate DDT, the bald eagles come back. We know that if you leave weedy margins in the edge of your fields, you see more sparrows. It's all connected. If we can just take the heel of our foot as humans and lift it a little bit off of nature's neck, it thrives because we're part of a system that's bigger than us. You learn that as an ecologist. You see that every year as a farmer. Those are the common threads that have shaped my life.

MF: Fantastic. Thank you so much.

WY: Thank you. Great to have you along today. Thank you so much.

MF: Oh, thank you for having me. This was so fun.

Bird-inspired Music of the Month

The live-broadcast of this episode on WGXC opened with Sparrow Sparrow by Malena Cadiz, a folk singer/songwriter from Los Angeles, CA, and finished with Let There Be a Moving Mosaic of This Rich Material, a piece from the 2022 album Words and Silences by Brian Harnetty which features spoken words by Thomas Merton, an American Trappist monk: To renounce more and more the temptation to give definite answers and to be more and more humble and honest in the search for the relevant material, which may suggest here and there good ideas or possibilities of new approaches.

Share this post