This episode is a special UK edition, as I was traveling there for most of October. My guest is Rachel Winkworth, an artist and avid birder who lives in Montrose, Scotland. The love of birds has been in her family for generations, passed down in the forms of nature books, some dating back to the late 19th century, and encouragement for the power of observation. Her family stories also give us a glimpse of what birding was like without binoculars in early to mid-20th century England. We hear her treasured memories of birds, beginning with her childhood in the New Forest (she was an 8-year-old RSPB member) and of her grandmother, a working woman and single mother who traveled the world in the 1930s with her bird guides in hand.

This interview broadcasted on October 26, 2024 at Wave Farm's WGXC 90.7FM in upper Hudson valley.

Interview Transcript

Rachel Winkworth: My name's Rachel, Rachel Winkworth, and I live in Montrose in the county of Angus in Scotland. Although I haven't always lived there, that's my home now.

Mayuko Fujino: And you’re originally born in ...

RW: In the south of England in a town called Fareham in Hampshire.

MF: So that's where you spent a lot of time with your family, your childhood?

RW: No, I was about 5, 4 years old when we left Fareham and we moved to a small market town, also in Hampshire, called Ringwood. We lived there for about nine years. My father was a policeman, so he moved with his job and as children, you know, the family, we all moved to Ringwood and then from there we moved to a village called Sway, which is also in Hampshire. And it's in the New Forest, within the confines of the New Forest, right on the very edge of it, the south western edge. And we lived there for about 10 years. So you could say we grew up in Hampshire, close to the New Forest, or in the New Forest, which is a large forest, which used to be a hunting ground for the king at the time, going back to centuries ago.

MF: Right, you had a book of New Forest.

RW: Yes, yes. It was by John R. Wise. It's called the History of the New Forest. It was published in about 1868, the first edition, and my mother had two copies. One was given to my sister and I had one which was a third edition published in 1888.

MF: When I visited your place, (I saw) you had lots of books, they’re all from your family members, the bird books and nature books. And so we were chatting about how your parents loved nature and how their love of nature nurtured you to become a birder. So I wanted you to talk about how you started birding.

RW: Yes, well, we were quite, quite young. My mother and father, they both loved nature and would encourage us to read about it. And if we saw a bird, then we would have to find out what it was. We would buy a bird book, or they would buy it for Christmas for us or for our birthdays, because we didn't have a lot of money. So in the days before the Internet, that was the way that we identified our birds. Also I joined the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds when I was quite small. I was about 8 years old, I think, maybe 9. But I still have my old Royal Society for the Protection of Birds identification. It's like a little chart book. So when you saw a bird, you would put a tick against it, and where you saw it, the date and the time you saw it. It was very basic, but it sort of encouraged us to make notes about what we saw.

And my father was good at woodwork so he would made us a bird table. It was in the garden at Ringwood that I remember the bird table being placed. And we would see birds like a Hawfinch on the bird table. The ordinary birds, sparrows, goldfinches, greenfinches, chaffinches, you know … wrens, robins, blackbirds, thrushes, all these birds would visit the garden. Hawfinch today would be quite a rare sight, but in those days it was probably quite common.

MF: And this is around what year?

RW: It would be around about 1960.

The winter of 1962 was very cold and very snowy winter. It went down in the record books as being a very bad winter. And it went right through till early 1963. There was a lot of snowfall all over Great Britain. It was so cold that the sea froze in various parts of the country and it had a great effect on the birds population.

And I remember making a note in my little RSPB book about a blackbird with only one leg. My parents told me it would have been because its leg was frozen and the blackbird had lost the leg because of the severe weather. So this blackbird, I did a little drawing of it, a little sketch, and that's still in the book today. I'm not able to find it at the moment, but it's still there.

And also there was a story that went around then about the wren. The wren was very vulnerable because of its size. But what they used to do, they found that wrens were roosting together in a ball so that they would keep warm. Up to about 50 wrens could be found in a roosting somewhere like, I don't know, a little hole in the wall or something like that. And they would all pile in and keep themselves warm together.

MF: Must have been quite a sight.

RW: Yes, it would. I never saw it, but I remember the parents — or it may have been on the radio or something — I heard it.

MF: If it's so historically cold, you have to be friendly all of a sudden.

RW: Yes, you've got all sorts of strangers in there. But it was survival. I hope it worked.

And year by year I made little notes about what I'd seen. And then of course, when you become a teenager, your parents give you a little bit more freedom and then you don't keep up your notes. So that was a period when I stopped. But I still kept the keenness of looking for birds. And it was just a sort of a thing, which wasn't just going out and seeing as many birds as you want to go and see. I never made the tick lists that people had today. It was more just a deep love of seeing whatever bird it was, the commonest bird. And also it was about flight and about the ability of birds to fly and be free from the land — just the freedom that you have in flight. I always thought it was fantastic that birds could be so free. They also have a hard life, I know, just to keep alive, but… so, yes, that was that.

And then when I was a little bit older, I sort of went out on my own a lot, down to marshy places down on the south coast of England where you'd see all sorts of birds and waders and all that kind of thing. And I remember one day going down to a little town on the south coast called Lymington where there are marshlands. And there was a report went round — before the Internet, you had little newsletters — that there were snow buntings down in Lymington marshes. So I went down and actually saw them. That was very nice.

So over the years I've kept my love of birds. When you’re working you don't always have the time, but it's a great thing to go out and just to sort of observe things. You go on a walk, you go into the forest or you'll go down by the sea.

That's what I really thank my parents for, is the power of observation. Always to look — when you're out, look around you and see what's around you. A lot of people today just don't look and see little. The tiny little things in nature, like little beetle or, you know, a red butterfly, flowers, wildflowers. It's quite sad, I think, that a lot of people don't have these interests anymore.

MF: Yeah, totally. I started birding as an adult. So I know that you don't just know how to see things and observe things. You kind of have to be taught to pay attention. It took me some time to finally get around there. But I'm glad I did.

Have you always had binoculars?

RW: No, no, you see, we didn't have a lot of money and binoculars would have been expensive, even back in the early 60s. But I remember one pair that my father bought me at an auction sale at an old house. It was when they moved and they lived in Somerset for a little while. There was some old house there which had a house sale. and he brought this pair of, I think, military binoculars, they were quite compact and I had them for many years and they were my first class binoculars. Second hand, quite old, but they worked and so I treasured them. And then one day I dropped them and it broke the prism and that was that. But I kept them nevertheless. And it's only in recent years that I've had a couple of pairs of good binoculars. I don't have a telescope but I just, you know, manage with binoculars.

MF: But if you have the patience to just look and observe, you could get some insights into birds behavior.

RW: Yes, yes. I remember once when I was a child growing up to a place near where we lived, walking along a lane and hearing a little wren singing in the hedgerow and I stopped and looked in and there was a little wren's nest. You know, things like that stick in your mind.

And also we love natural history. I remember taking a grass snake home to show my mom and dad in a paper bag and they were horrified but of course they knew it was okay. But they made me take it back to where I found it and release it. Things like that, we just were fascinated by nature.

Another thing to mention about books is that my mother and father used to, at Christmas, they would buy me a bird book or something like that, you know, when I got a little bit older. And when I was 10, I had one at Christmas which was a lovely one with the illustrations by — it's one of the famous old artists whose name I can't remember — but the most beautiful color illustrations in this book.

And my mother had several bird books that she used, and we'd annotate on the pages where we'd seen a rare bird. We'd annotate what we'd seen. I remember when we were going up to Derbyshire before the M1 (motorway) was built and we used to go all the way through the countryside up to see my grandmother, my father's mother, and seeing birds on route that we'd make notes on. I remember seeing a Montague's Harrier, which today is very rare. But those were the things we would make a note of in our bird books. So alongside the descriptive the birds, you'd have the date you saw it, where you saw it, and there's a lot of that going on there.

I remember when I was nine, going to a place called Harbridge, near Ringwood, where we used to live. Beautiful area of marshland alongside the River Avon. And there were a lot of snipe, redshank, all sorts of waders and wildfowl there. But the exciting thing that we saw there was a water rail, and I never forgot it. It was in a boggy ditch with a little stream running through it. And we were on this little bridge and we looked over and there was this little water rail with a red beak, and it was just a lovely sight. We were so excited, you know, because we’d never seen one before. Things like that, you never forget. And it's only recently since I've moved to Scotland that I've seen them again, quite often. So that was very good.

So, bird books, I had the Observer's Book of Birds, and I had this lovely little book that I showed you the other night, who's artist I can't remember the name of. And then I had another one which was called Watching Wildlife, and it was how to observe foxes, deer, badgers, stoats and all the weasels, to observe them with the wind in the right direction so that your scent wouldn't go to them, so the scent would have to go coming towards you, you know, all these little things and what their footprints look like, all this sort of thing. I was absolutely thrilled with it. I still got it now.

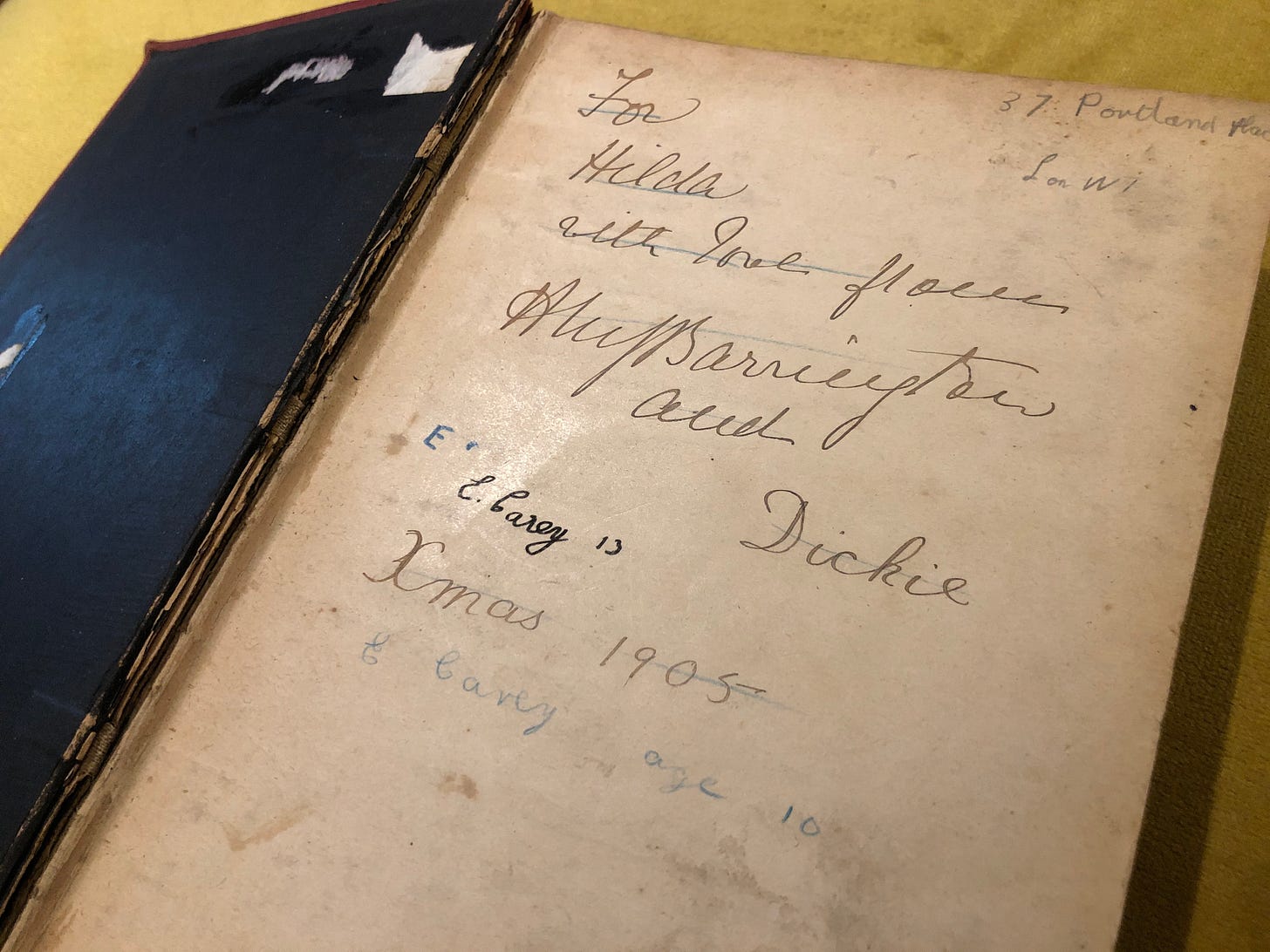

When my mother was small, she was given a bird book by her mother, my grandmother. And it's a lovely book which I've still got. It was my grandmother's book, she was given it when she was 10 years old, and then when my mother was 10 years old, she gave it to her.

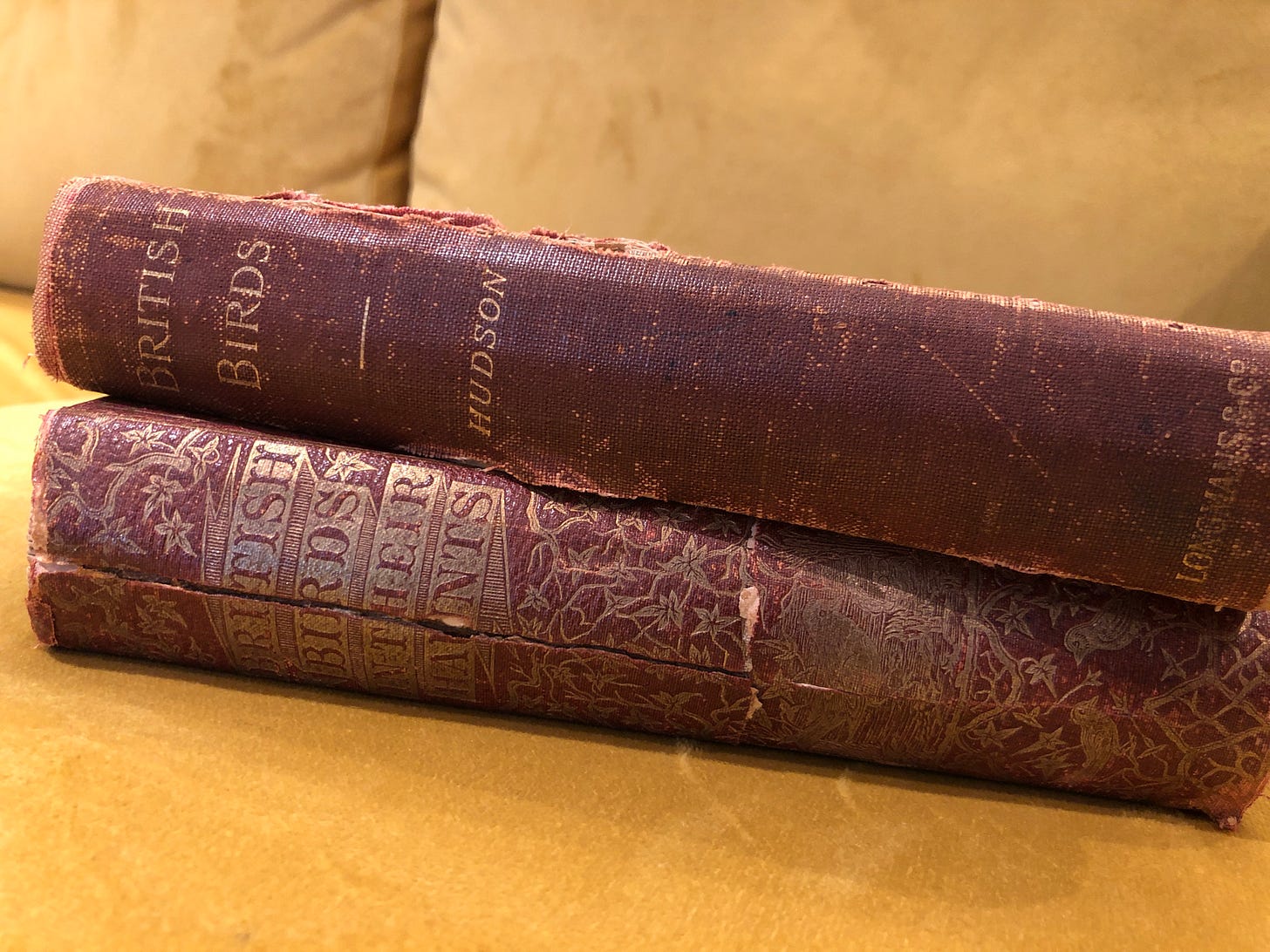

And then when my mother died in 1999, she gave it to me. Well, bequeathed it to me. So I've still got it. And it's a book which is written by a very famous writer of the day, going back to the Edwardian era, late Victorian / Edwardian, W.H. Hudson. He's well known in Britain as being a famous writer of natural history and also country life, mostly in the southern counties.

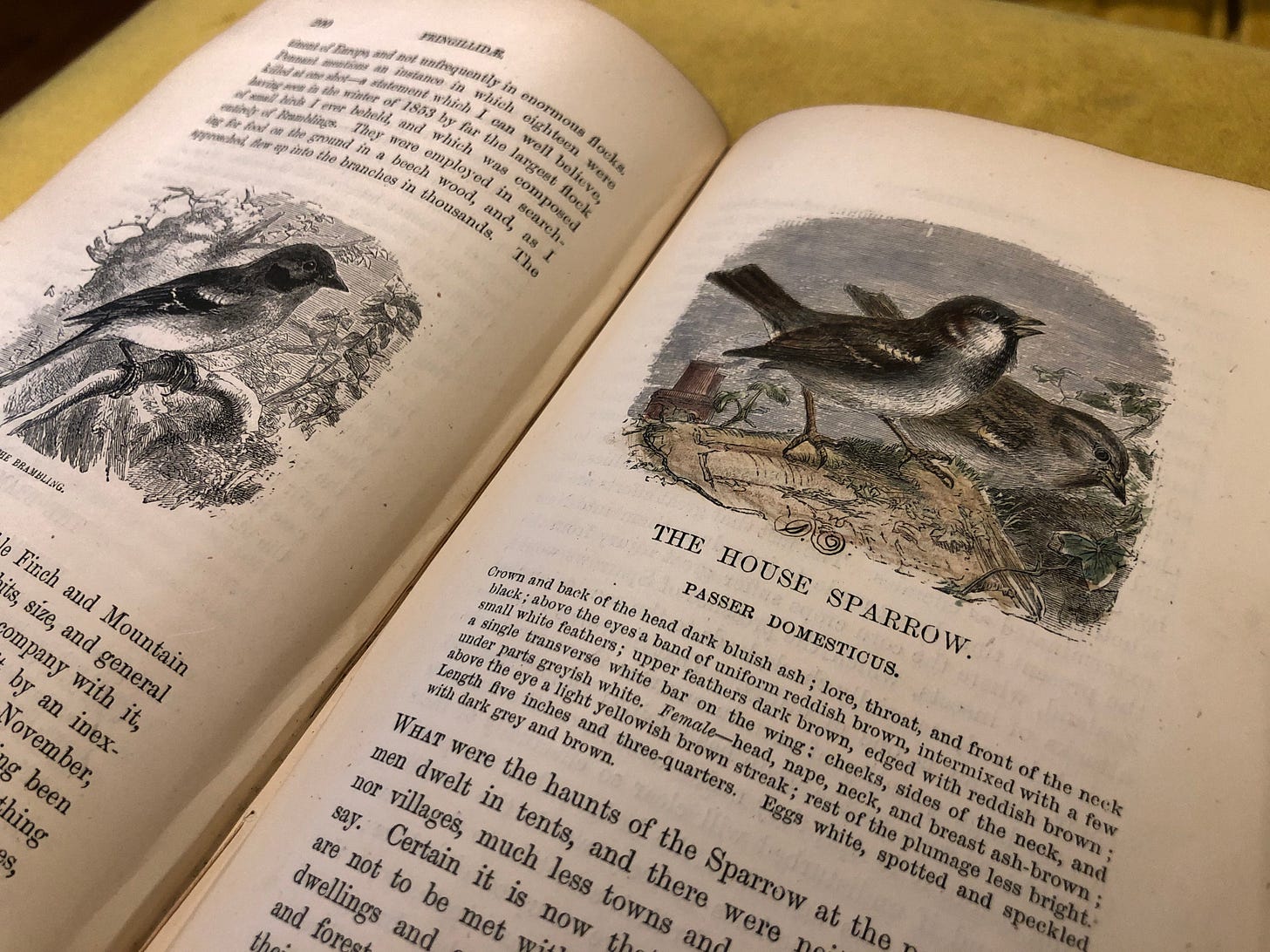

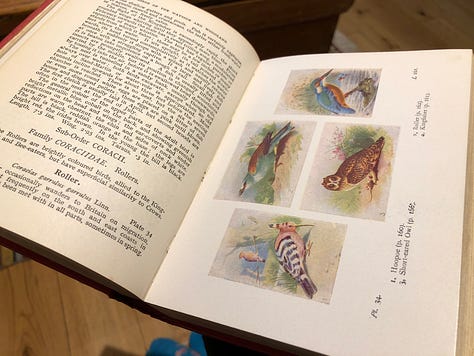

And then another bird book I've got, which is a real gem, is Birds of Great Britain, I think. (“British Birds in Their Haunts” - we didn’t have this book on hand at the time of the interview.) But it also includes the Egyptian vulture and some other vulture.

MF: How are they included? British Empire all over the world, they mean?

RW: Probably. It's got a beautiful cover. It's sort of dark red and it's got gold tooling on the spine. It's got a golden eagle in gold relief on the front, and most lovely wood cuts — well I thought they could be wood cuts — really beautifully done and some of them are hand tinted in watercolour. It's very precious book to me. It's a real gem.

My parents bought it in the county town of Wiltshire, Salisbury, in a bookshop called Beach’s, which was situated in the heart of the old city of Salisbury, near the cathedral, right on the corner of a crossroads. And I remember it was a old timbered, half timbered building. My parents used to go there quite often because they loved old books. And so we were taken along too. And that's what gave us our love of books, my sister too. And we'd go in and it was like going on board an old galleon. You had creaking timbered floorboards which were sagging. And these old bookcases all on the ground floor, little corners where you had bookcases at right angles and all different subjects. We'd always go to the natural history ones and we'd look and my parents would put out these old books. And that's where they got this lovely book for me, which I treasure, you know.

And my mother told me that my grandmother also loved birds, which seems funny. It must be inherited. Must be in the blood or something. My grandmother, who I never knew because she died in 1949.

MF: Do you know when she was born?

RW: She was born in 1895 in County Dublin in Isle of Southern Ireland. She lived there for some years. Because I never knew her or her parents or any of the family, there's a lot of guesswork involved, so it's difficult to give an accurate history of her Irish life. But she did go to school in Exeter in Devon (in South West England) and I know she was confirmed in Exeter Cathedral and so she had some family friends in Devon.

And then she was a nurse during the First World War. I don't know any details of it, only a small photograph that my mother had in her in the album.

MF: And that's quite a lot of photos, actually, from that time period.

RW: Yes, very lucky. Although I don't know who took them all, you know, and it's all a bit of a mystery, but it's a fascinating mystery.

MF: So you said it's a guesswork but you have a lot of materials to make the guesses based on.

RW: Yes, and I've had help from a friend who has done some research, but it's not a full sort of research, you know. But anyway, after the First World War, I presume she lived in Dublin or thereabouts in County Dublin. And then she joined the Merchant Navy around about 1926 and she went to sea. She was on the old strath boats, they called them, or the ships that they were passenger ships but also I think they were mail ships. The old P&O line* was founded in 1837 and she actually went through the Second World War as a merchant seaman. And she got the Atlantic Star and the Pacific Star which were awarded to merchant seamen who had completed certain Atlantic or Pacific journeys. They had to have done it for six months to achieve the medal after the war.

*A British shipping and logistics company dating from the early 19th century.

I only knew this because I inherited a medal bar and I think my nephew's got her medals. The Pacific Star medal was given because they did a lot of troop runs. They took troops, New Zealand and Australian, I think, from the Solomon Islands. And then I suppose the Atlantic would have been to America, obviously, New York perhaps, I don't know.

MF: There were many photos of even Japan and Hong Kong. And I wonder when those photos of Japan was taken, because if it was the second War, I don't know how she could have landed.

RW: Well, that would have been during the time that she joined in 1926 through til 1939, because she died in 1949 after the Second World War. So those were in the peace time interval between the two wars.

MF: So those must have been the time, because there are lots of like street scenes.

RW: Well, if you remember, some of them are 1933. It's actually written in the book by her. So she must have visited them in 1933. And some of them I think are postcards, not actually taken by her. But I know she had a camera. Some of the smaller ones, perhaps, were taken by her.

MF: It's so extraordinary thing to think about that she had a job — I mean, we don't know how she applied for this job, but — she seemed to be a really independent woman. She was traveling all over the world — probably watching birds, I would like to think — looking at all these foreign countries. A very adventurous person.

RW: I think she had a spirit of adventure in her. That's why she wanted to do it. And I think she wanted to see the world because I think her brother was in Ceylon before the war. He was a civil servant. So whether that had anything that influenced her to want to go and see the world, you know, maybe. But yes, yes, she had a spirit of adventure, definitely.

MF: And she was also a single mom.

RW: It must have been very hard. And from our modern day perspective, we could criticize her for leaving her daughter, in the care of good friends but not seeing her very often. When she did come back, she would bring her gifts, you know, things like that. But she didn't get the home care and love and attention from her mother. But then when you think of it, it was such a taboo thing to do in those days to have a child out of wedlock. And because her family were quite probably Victorian in their outlook, and also there was certain status of the family to take into consideration, she was set adrift and would have to have earned her own keep. And in order to do that, to support her child, maybe she helped … well, you see, I don't know whether that's true because when my mother was born after she was already ... or was she? I don't know, I wouldn't like to say.

But it could be that she felt she had to continue the work for financial reasons. Yeah, let's say that. And that she was trying to do her best for her child. I like to think of it in that way.

MF: It is hard to tell because we don't know what options she had at the time. If a woman wants to find a job at the time, couldn't she find a job that doesn't require her to be traveling all over the world? I want to think that's what she wanted to do, that she wanted to see the world rather than staying in a little town and, I don't know, pick up a sewing or cleaning job or whatever.

She was also not very young when she had your mom. (*She was 30 years old.)

RW: No, that's another thing. Maybe she loved her independence but felt that she wanted a child. And she had a love affair with someone.

MF: And she didn't marry the guy.

RW: She didn't. But we know him … we don't know him, but have all the photographs of him. And my mother told me that he supported her in her education.

MF: Which is another really interesting thing.

RW: He didn't abandon her. But I think what happened was the war, the Second World War, and that's what separated lots of people. You know, there was a crazy time.

MF: Right. The separation came because of the war. But not marrying — again, we can only imagine, but — she could have married him. But she didn't. For some reason, this woman was a very independent person. And it's not like she didn't have a relationship with him. They had a relationship, it just didn't take the form of marriage.

RW: Yes.

MF: Which is, for the time…

RW: Yeah, yeah. It's quite unusual. Yes, I think you're right. I'd love to have known her.

MF: And I want to know what birds she had seen during the trip. I mean, she must have seen a lot of “lifers,” as we say.

RW: She had. I've got one of her books, which is about ocean bird life and marine life as well.

MF: So she must have been observing from the ship.

RW: Yes. I wonder what she saw. She would have seen albatrosses, obviously, the birds of India. She went, sort of touched on the countries of India and Australia, and I know she loved Japan. It was her favourite place in the whole world to go to.

MF: It's kind of wild to think that she must have seen lots of Japanese birds.

RW: There's a picture of a kookaburra in the album. And there was, coming back to Ireland, there's a little canary, but what else?

I know she had a little chipmunk as a pet. I think it was called Billy. I'm not sure, but it might have been called Billy. I've got a pencil sketch of it somewhere.

But anyway, so, yes, birds connected us all through the ages.

MF: Some of those people, your great great grandmother or somebody gave your grandmother the bird book, because she was 10 in 1904 (correction: 1905).

RW: That's right, yes.

MF: So maybe your great … who would that be? Great great grandma?

RW: Yes, it must have been.

MF: … must have been, possibly, a birder.

RW: Well, it could be. Would be lovely to know that.

MF: It's quite a beautiful history of a birder family, I would like to say.

RW: Yes, yes. And it still goes on, you know, my sister lives in Spain and she looks out for birds there and sees lots of blue rock thrushes and things like that. I'm very envious.

And when I lived in France, I had a black woodpecker visit the garden on a few occasions. I'd never seen one before and I was absolutely thrilled to see a black woodpecker. And we had an old apple tree which had disintegrated almost, and we just had a stump about 6 foot tall left. And this black woodpecker would come and its beak was enormous, it was really long, and it was a huge woodpecker. And it would get right down at the base and it would peck at this wood, which was rotten. And he reduced the stump to practically nothing within a few days. And then he came back occasionally over a couple more years.

And then just before I left France to come and live in Scotland, I heard him calling in the woods. And it's quite an extraordinary call and it's very distinguishable … and it's like a farewell. It was quite sad to hear it, really. I never see it again. But there were lovely things like that to see in the garden there. Crested tits that I'd never seen before. And we used to get red squirrels in the garden with their family of kittens, you know, all sorts of lovely wildlife there.

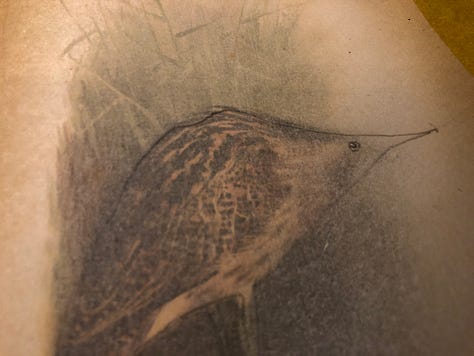

And about a winter before I left France, I went down to a place near Avranches, which is on the coast of the Cherbourg, just at the bottom below the Cherbourg peninsula. And I was down there on my own on a winter's day, and I was walking between these two reed beds with a gravel track in between, and I went into a little sort of cavity of the gravel and stood there. And a bittern flew up right in front of my face. I could have almost touched it, this bittern, and I'd never seen one before in my life. And it flew up and I was just astonished to see it. And it flew away. Great big flapping wings, you know. Oh, it was wonderful.

MF: Do you have bittern in Scotland too? I saw it in the Oxford (University) Museum (of Natural History) … taxidermy, not a real one.

RW: Very rare, very uncommonly, I think. I think there was one at Strathbeg (Nature Reserve in Aberdeenshire, Scotland.) Going back to the spring, we seemed to have had a bittern explosion in the United Kingdom this last spring and summer. There have been bitterns in all the nature reserves around England, it seems, and only a couple in Scotland, so it is quite uncommon here. But yeah, they’re lovely things to see.

MF: It will be soon winter … We're doing this interview in late October in Aberdeen. So around this area, is there any bird you're looking forward to seeing in coming months?

RW: Yes, the waxwing, which is a beautiful bird. So, so smart. And it's plumage is quite unique because it looks a smoother smooth. It almost looks like it's modeled out of clay, you know, well, porcelain or something. And I only ever seen them once before in Woodstock, in America.

MF: In Hudson Valley.

RW: Yes, yeah. But that was the American version. But so I was really thrilled the year before last to see them in Montrose and Aberdeen. And I hope we see them again this winter.

MF: And those ones you mentioned, is it Bohemian waxwing?

RW: Yeah, I think so. They'd be coming from Scandinavia, I presume.

There's all sorts of birds that I've seen here that currently at Montrose Basin, which is the largest Saltwater Basin … or second largest? Well, I think it's the largest in the UK. They're hoping for at least 80,000 pink-footed geese to visit this winter. And we watched the skeins going over and the call of the wild goose. And that took me back to childhood when we lived at Ringwood. On a winter's night, my parents, probably before we had television maybe, they'd say we can hear them. And we'd all go outside into the garden and we'd look up into the night sky and I can't remember if they actually saw them, but these skeins of geese were going over calling, probably pink-footed geese again. I'm not sure, but it was like the call of the wild goose and it took you back to childhood. It's a lovely memory.

MF: Thank you so, so much for sharing all these beautiful stories.

RW: Thank you very much for inviting me. It's been a pleasure. And long live birding and the call of the wild goose. Thank you.

Some of the books mentioned in this interview

Birds of the wayside and woodland by T. A. Coward (Internet Archive)

British Birds by W.H. Hudson (Internet Archive)

British Birds in Their Haunts by C. A. Johns (The Project Gutenberg)

Bird-inspired Music of the Month

Music released in September 2024 by Glasgow based Turkish musician and sound designer Isik Kural (RVNG Intl.), and Kitchen Cynics & Margery Daw, Rachel's collaborative music project with Alan Davidson (Cruel Nature Records.)