Beakuency welcomes George Steele, an environmental educator based in Amsterdam, NY. It's almost time for the Christmas Bird Count, one of the oldest citizen science projects. And there is no better person to ask to talk about it than George. He has been a part of it for decades, traveling throughout New York State and beyond to assist many local groups in their efforts, including the counts right here in the Hudson Valley. We also hear about his nature education programs, and his work to build a world where youth are inspired by the wonders of nature and become environmental leaders.

This interview was recorded on October 31st, 2024 in Catskill, and broadcasted on Wave Farm's WGXC 90.7FM on November 23rd, 2024.

All photos in this article are from George's Facebook page, posted with his permission. To learn more about his work as a nature educator and upcoming events, visit: www.facebook.com/george.j.steele

Find out the CBC near you in the Hudson Valley here.

Interview Transcript

George Steele: Happy to be here. I'm George Steele. Older people will recognize George the Animal Steele. He was in the 60s and 70s. He was one of the pro wrestlers. There's Olympic wrestling, which is totally separate, and then there's the WWE. I'm not even familiar with it, you know, the chair smashing wrestling. And back in the day, these wrestlers, there was a whole host of them that would go around and do venues, local, small venues, like a high school gym, and they'd have it and be a fundraiser for someone. So he became very famous as George the Animal Steele.

Mayuko Fujino: It's not like your parents named you after him or anything, right?

GS: No, George goes way back to my grandfather from Connecticut, and my dad then is named after my paternal grandfather. And then first born, I'm named after my dad.

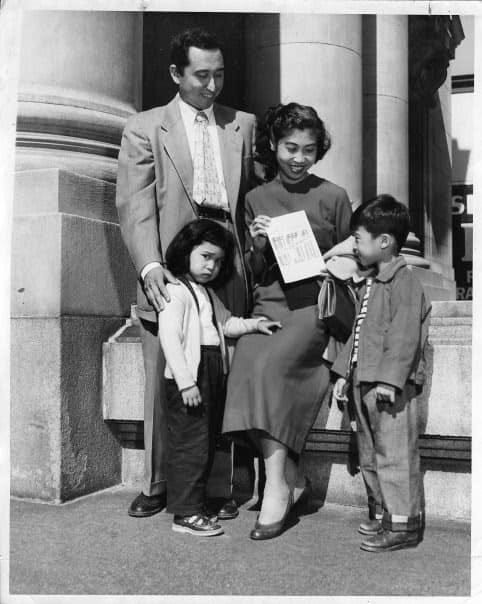

My father was an American born in the Philippines. My paternal grandmother was Filipino, but my paternal grandfather was an American, and he went to the Philippines in the early 1900s. The way I envision it, it was like the Peace Corps of its time. And the Philippines was an American - not a colony - it might have been classified as a protectorate that the US had gotten control of it after the Spanish American War. Because of its significance as a naval strategic spot, the United States wanted to bring the Philippines into the 20th century, teach everyone English, and become basically a friend and ally of the United States. So young men went over to build roads and build infrastructure and educate. My paternal grandfather ended up going there, building schools and supervising schools.

Then my dad, after World War II, came back to, or came to the US and never got back to the Philippines. That's sort of how I ended up here. All of my relatives on my mother's side, my father's side, my aunts and uncles, all were bilingual. They all learned English in elementary school. My mom is Filipino, came to this country and became a citizen. I was maybe about six years old, I think five or six years old when she became a citizen, but grew up here in New York State.

And for whatever, they never taught us Tagalog or Bikol, which is the regional dialect that they were from. So unfortunately, English is my only language. I took German in high school and was able to pass the New York State Regents requirements for it. But I would have to use digital translations if I were to travel in Germany. But it's amazing now what they can do. I go to schools and there'll be students from other parts of the world and teachers will have basically a translator, a cell phone translator to be able to facilitate the connection for some of these kids.

MF: This is a school that you’re involved in for your nature education thing.

GS: Right. What I do for the bulk of my work is elementary schools. I've wrapped up basically my programming for the year because we've got Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year's holiday. That just shoots the whole school schedule. So I just finished up with some schools down in Wallkill, south of New Paltz area. And then in January I'll start up, I have a school in Pennsylvania and then a mix of different schools, mostly here in the Capital Region area through April, May and then June. And then in the summertime I'm doing a lot of library programs and summer sessions. I do some things at the Great Camp Sagamore, which is up in the Adirondacks, and I do some things with some children's camps.

It's interesting, there's a woman I've known for many years and she's an Episcopal priest. She was a deacon or she wasn't ordained at that point, but she was very involved with an Episcopal Church and they were doing vacation Bible camp. But she wanted to do it with a theme of God's creation. So I said, sure. I mean, doesn't matter in terms of your religious bent, the natural world and all this wonder is a wonder, no matter where you want to have it come from. And so I did that for a couple years. And then she moved away into the D.C. area. So she just got a hold of me about whether I would want to do a one week nature related program. So it'll be interesting to see, that'll be down in D.C.

MF: But you also have some programs for the public outside the school system.

GS: Yeah, I do, like the one at Landis Arboretum, it’s a small, not for profit arboretum in the Schoharie Valley. I do several programs in the months from April through October. My first program every year is bird related, it's a spring hawk watch. The Schoharie river is a north south corridor, so birds will use physical features like that as part of their migration strategy. It's not the best hawk watch place, but it's a fun place. I do that in April.

And then I always end the year - the warm seasons - with a Halloween Owl Prowl. So just had that last weekend. I think there was maybe twice a barred owl responded, but it was sort of hard to say, because it wasn't very responsive. I mean, if you get barred owls responding, you know without a doubt, because they're hooting and hooting and hooting. The barred owl call, the books describe it as “who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” (Mimics the owl call.) And sometimes, especially late in the year, late in the growing season and winter, you just get the “whoa” part, which is the tail end [of the call], which I think - I'm not 100% sure, but my hypothesis is - that's younger birds not yet confident with their calling because they're declaring territory and saying, “hey, this is where I live.” And so if you're a younger bird, it's like, “well, maybe… whoa!” So we heard that twice. Sometimes you get the owls really cranking up, at other times you don't get anything at all. But it was a gorgeous night, so it was fun.

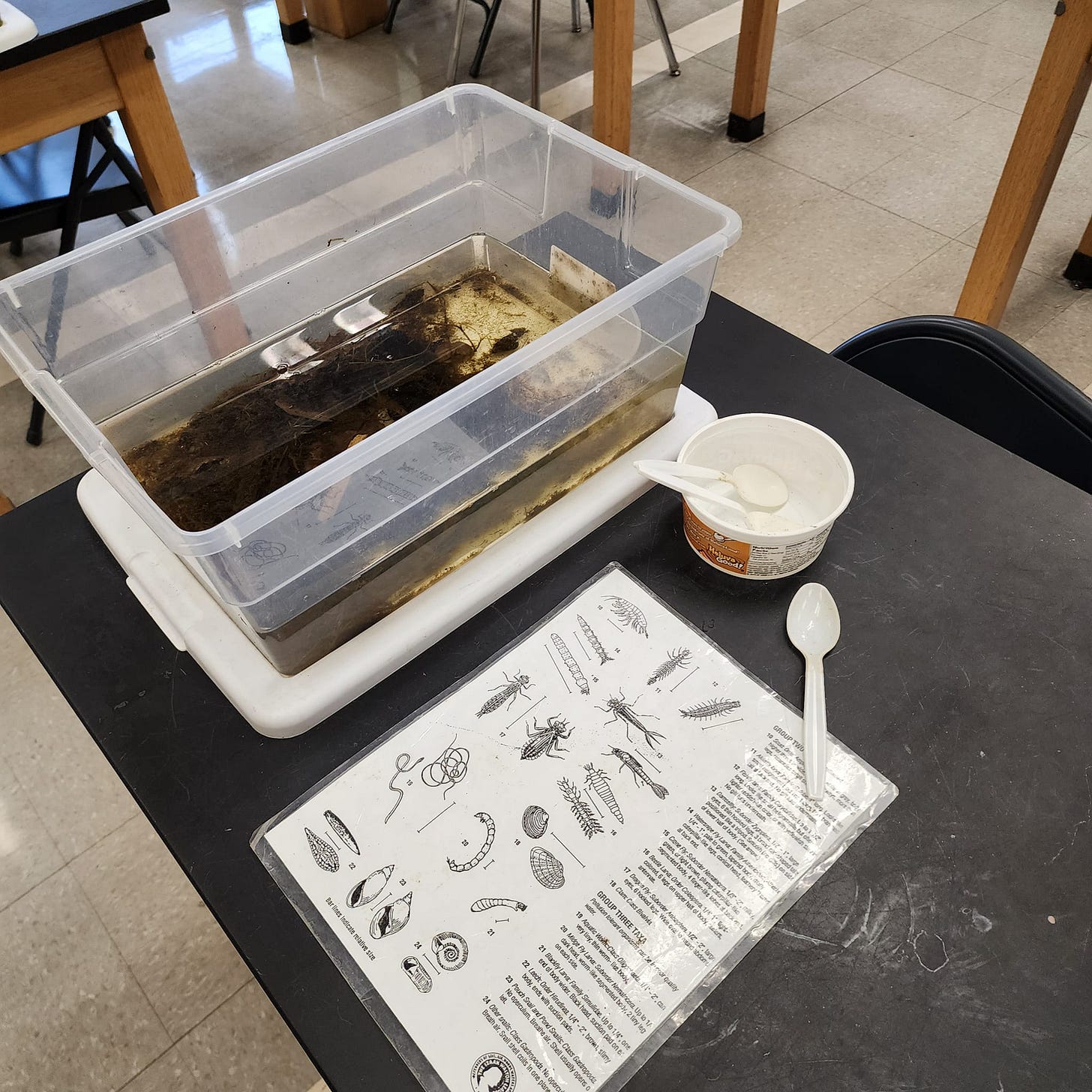

My background is in forest ecology. I tell kids and teachers that when I was in college, I did all the ologies: mammalogy, ornithology, herpetology, entomology, ichthyology, limnology, soil studies - there's a name for ology for soil studies, I forget what it is. But so for the general public at, like, the Landis Arboretum, I'll do a wide range of things. One of my favorites is to do a pond ecosystem, aquatic macroinvertebrates investigation. And then another is to do a forest walk looking for reptiles and amphibians. So it's a wide range of things.

MF: Not just birds.

GS: Yeah, not just birds. In the last, maybe 10 years, I've done more programs for other organizations. For example, the city of Amsterdam, in conjunction with the Amsterdam Public Library, I'll do a first Saturday of the month bird walk along the Mohawk river, which is interesting because part of the features is that there's a peregrine nesting on the bridge, the Route 30 bridge that goes over the Mohawk River. So it's fun to see the peregrine, some of the activities, see if it's the young in the nest and things like that.

MF: You're around Albany area, so most of your programs take place around there?

GS: Mostly in Albany area, yeah. I live in Amsterdam, which is west of Albany. That's 20 miles west of Albany or so. I have a note from the Vale Cemetery in Schenectady. For several years I've done a bird walk in the Vale Cemetery, there's a big wild area. The Vale Cemetery is sort of really interesting historical site in terms of people there. But cemeteries are a great birding place because you have a lot of green space, huge trees and so oftentimes cemeteries will feature bird things. Someone's been asking me to do one at a big cemetery in Amsterdam, but I haven't gotten around to doing something there, I should scout it out at some point.

MF: When I started birding, I started in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. And it was easy because like you said, it's open.

GS: Well, especially in an urban environment like New York City, you know, the whole metro area, whatever little green space you got, if there's birds around, that's where they're gonna go. Because some of the birding like in Central Park, I mean, you can't beat that birding. You come up here [in upstate NY] for warblers in the springtime and you struggle to find things anywhere here because who knows where they could be.

MF: Yeah, I found it difficult to figure out where to go. That's why I joined the bird club. Which I didn't do in New York City. When I came here, I was expecting to see - well, since this is countryside - a lot of birds, and then it's like, “where are they?”

But it was actually helpful because for the first time that made me think the relationship between birds and their habitat, which I didn't have to think about before.

GS: Right. In New York, it's basically, it's green and there's insects and seeds there. But here, you've got birds that are going to want forest, versus edge, versus wetlands, that kind of thing.

MF: yeah, it sort of gave me the idea of birds not existing in a vacuum, but part of this bigger picture.

MF: I wanted to ask you to talk on the radio because of the season too. Marian (Sole) told me about you a year ago when you both went to Christmas bird count. So first, could you tell the listeners what the Christmas bird count is in the first place?

GS: It's organized by the National Audubon Society. It's a community or citizen science event where people will go to a specified area that's been identified and sanctioned by the Audubon Society. Because if you're doing some kind of study of what numbers of birds are there, you don't want an overlap of areas because then you'd be double counting.

The Christmas bird counts historically go back to a time when birds were often shot just as a means of practicing your marksmanship skills, in addition to the use of feathers for hats and things like that. This is going back to the 1930s. The first Christmas bird count was something like 125 years ago, started by some ornithologists saying, well, let's sort of create a tradition to break this thing of shooting birds and instead count birds.

And from that has sprung this community science where people can go and count birds. And the data is used by ornithologists to get a feel for what's happening with birds and the population of birds. So in a Christmas bird count, it's a 14 mile diameter circle - might be off by, I think it's 14 miles - and it's divided up into sections and teams of people go, and you look for and identify and count every single bird you can find.

So some of the counts I've done, like there's a count that includes this area, the Greene county count, and…

MF: This is organized by local clubs?

GS: Local clubs, sometimes it's university people. I do a count out near Oneida which is Turning Stone area, and I think it's a professor from Hamilton College that coordinates that one. But it's usually a bird club that's doing it. Sometimes it's a local bird club or an Audubon related bird club. I do the Montezuma Christmas bird count. I worked on releasing bald eagles at Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge back in the 70s. So when I heard about the count, Christmas bird count there, I was like, oh, I'd love to help out with that one. And that one is focused around the DEC’s Nature center that's actually run by National Audubon. So it's a Montezuma Audubon center. So in that case it's sort of a combination between a state run thing with Audubon really taking the lead on it.

MF: Sorry that I interrupted you, you were going to talk about the Greene county count, and that was organized by who?

GS: Greene county count, I think, is Mohawk Hudson runs - Oh no, no, I think it's sponsored by the Audubon group that's in this area. Larry Federman is the compiler coordinator. And I know that most counts will have a gathering at the end of the day. So theoretically the Christmas bird count is set for a specific day. The Green county count is always the first Tuesday of this period. It's an 11 day period before Christmas to 11 days after Christmas. So it starts December 14th. It ends January 5th.

Up until Covid times, you'd start off at maybe four or five in the morning to try to get some owls, and then it'll usually end just after dark in terms of getting the bulk of the diurnal or daytime birds. Some people might still go out and try to call for owls later that, and then report their numbers to the person in charge of adding up all the numbers. So most clubs or most counts you'll end up gathering up someplace, at someone's house or a restaurant, having a dinner or whatever. And Then reporting your numbers. There's all kinds of traditions about how you report your numbers. It gets somewhat competitive, although in terms of the statistical analysis, it shouldn't be competitive because, you know, it doesn't matter. You're not like trying to find that one bird. You just, what are the birds out there? But human nature. You want to say, “hey, we got a bird that you didn't get” kind of a thing.

MF: So each county, each region has their own count, and I wanted you to talk about it because you're kind of like a mercenary of Christmas bird counts. You go many places and join…

GS: Last year I did 13 Christmas bird counts. And the maximum you can do is theoretically 23. 11 plus 11 plus Christmas Day. I haven't found a place where anyone's doing Christmas bird count on Christmas Day. But last year I did a count on New Year's Eve and on New Year's Day. Two different counts. Yeah, so I help out. I'll look and find a Christmas count [and if] my schedule’s open, I'll say, can you use a hand? Part of it is the challenge of finding birds, but part of it is just to share finding birds with other people. And, you know, I'm well known for hooting and whistling for owls, and people are sort of enamored with that. So I guess there's a little bit of ego in there, trying to find something. And just also, extra eyes for seeing things, it's always helpful. And there is a knack for just catching something out of the corner of your eye or whatever that not everyone has. So just sharing that and helping people find birds for their count.

MF: You live in Albany area. I heard that you were in Dutchess county, maybe Clermont or something, at 4am last year for a Christmas bird count.

GS: Well, actually, I did a count in New Jersey after doing a count - where did I have the count the day before? I forget where the count was the day before - Oh, the count was near Buffalo the day before. So I drove back here or halfway down to New Jersey and then met up with people there.

It depends on which count. Some counts you meet up with a team at say, 7:00. But like for the Greene county count, I know that I'll be meeting up at like 5 o'clock in the morning. So, you know, that's about an hour's drive from home. So I have to get up at 3:30 to get ready and then drive there. And then I'll usually get there a little bit early and I'll start to hoot and whistle for owls to see if we can get a screech owl to respond or a great horned owl.

And then my partners will come in and we'll start up with trying to still hear an owl or whatever, and then move on from there.

MF: What's so special about the Christmas bird count that makes you do all these? Is it kind of like a reunion with people maybe?

GS: Well, with some people, like I mentioned going to Montezuma. And the funny thing about going to Montezuma - years ago, Audubon would publish a magazine on just the Christmas bird count. It would run down the numbers where all the different counts were and listed people that participated in the count. So if you paid the $5 fee - you could do the count without paying any money, that's fine - but if you paid the $5 fee, then you would be listed in this little magazine. It was a fairly hefty magazine, you can imagine. And so I'm looking through one and it says there's a Montezuma count. It had a contact person. So I sent an email to this contact person. I says, “I see that you do the Montezuma count. I'd love to help out. Could I help out?” And right away I get this email back, “who are you? Do you know anything about Christmas bird counts?” It was like, whoa. So I emailed back, well, yeah, I do a lot of Christmas bird counts in the Albany area. And I mentioned several people that are well known in the Albany area that I've done Christmas bird counts with many times. And then I get an email back, “oh, I know you and sure, you can join my team, but there's another gentleman who could use a hand with a couple people on his team.”

And so she gave me his name and I'm going, oh, I know him because I used to work with endangered species, he worked for the DEC as a biolith biologist and then now was working out there. He's retired now. So again, it's one of these things of, you know, you do enough birding and you run into people at different places and they'll know someone that you know, or you'll run into someone that you knew 20 years ago. It's a small community of people that are dealing with natural science and particularly where nature and education come together, working at nature centers or places like that. And they're very likely people that do Christmas bird counts along with other kinds of events.

There's the breeding bird Atlas work that's going on. And I didn't really help out much with this, this go round the breeding bird Atlas*, but in the past I have. I sort of feel guilty that I didn't do as much with it.

*The third New York Breeding Bird Atlas, 2020-2024.

MF: Well, if you're doing 13 Christmas bird count, I think you're doing enough.

GS: But yeah, it's a short period of time to do it. But with the breeding bird atlas, the commitment to a particular sector, trying to really cover it… it's a little bit more involved in a different way. You know, there's a different protocol, and you're looking for every single bird in the springtime, spring and summer, that's breeding in there, which is a whole other skill set in terms of bird songs and things like that. You know, I consider myself a good birder. Some people say I'm an expert birder. But I wouldn't call myself an expert birder. I mean, I'll be as much as anyone relying on Merlin, you know, the app to identify a warbler singing. Because they'll be like, “oh, I know, I'm pretty sure it's a warbler, but I'm not sure which one.” Some warblers I don't have the experience with.

MF: Whereas Christmas bird count, I found it a little bit easier for maybe beginners because you don't have to have all the knowledge of breeding behavior.

GS: Right. There's a much less number of birds. All these insect eating birds like the warblers, most of the warblers are gone. There'll be a few warblers that stay around and you'll try to find them. And then there's a few birds that are sort of accidentals, and again, multiple eyes seeing them, it's like, “oh, what's that one?” And as a team, you can discuss it if you're not sure.

When you talk to people about when to start birding, wintertime is a great time because you can set up feeders. So now you have birds coming in and there's less numbers of species, so you can begin to identify the ones that are regular visitors. And then there's ones that sort of hang around a little bit. Maybe not right at your feeder, but if you have like a forested area or a wetland area, a marshy area, you can start to look for a few other species. So it's a lot easier for a beginner in the wintertime trying to jump right into it.

MF: The episodes you shared so far make it maybe sound like… a beginner might hesitate to join. [But] you don't have to join at 4am.

GS: No, right. It depends on the team you're working with. But you're dealing with cold weather. Depending also to what kind of territory you're in. Some people will end up with a very suburban territory. So that's much different than if you're out in the countryside. Typical country - and I have lots of countryside sites - you're driving in a car. You usually don't have the heater on because that's making noise so you can't hear the birds. You're driving with the windows open at 10 degrees out, so you want to dress warm. And you know you're going to be in the field for the whole day. So there are some clubs, the Hudson Mohawk Bird Club is very inviting for people to come in, but they try to warn people. And then the coordinators will try to hook a new person up with someone who's more patient and more willing to, you know, and birders generally are very patient about that. But you know, it's a long day. Even if you start at say 10 and you go till 4, so right there, six hours, very cold out. It could be miserable weather, so just be prepared for that.

But some people can also help out by just doing a feeder watch. So they know that they're in the territory, and you're going to have a feeder and you watch it throughout the day. But again, you know, you don't keep like counting, “oh, I have 300 chickadees!” Because chickadee one, another chickadee, you're counting the same one. So, you know, it's a little bit different in that respect.

MF: That's good information to know because not everybody has access to go outside or some people are not tolerant of cold.

GS: Yeah. People can participate in it, especially if they are already going to be doing a feeder anyways. And it's so frustrating when you're actually doing - you're driving around in the country and you're looking for feeders because that's a spot to stop. And obviously you're not stopping at someone who was already doing a feeder count. You're just going through this neighborhood and you'll see a feeder. But many of the time the feeders will be empty. So it's like, oh, another empty feeder.

And when you find a feeder that's full, then, you know, you pull in and then it's… For me, being an educator, I don't mind [if] someone will come out and say, “what are you doing?” and I'll end up spending three or four, five minutes explaining the Christmas bird count, what's going on. And thanking them for [letting] us look at the feeder. We're not staring in their house, you know, you're parked in front of someone's house on the road with binoculars. I've never had an account where someone was negative towards me. I've been pulled over by police, by sheriff saying someone reported someone driving around in the community. And I'll explain. Actually this one case, they said, well, hold it here for a second. And they called into their office and someone did a bit of research and found out, yeah, there is this thing called the Christmas bird count.

Some people will put a sign in the car, you know, “Audubon Christmas bird count” kind of a thing to try to at least ease up some of those kind of things if you're in a particular area. But yeah, I've heard of stories of people really grumbling at people stopping in front of their house, counting birds at their feeder or whatever. But I've never experienced that.

MF: If you want to go hardcore, join a team wherever closest to you. And if you don't want to go hardcore, you can stay home and count birds with your bird feeder. Or you can just fill your bird feeder.

GS: Definitely. Even if you're not going to count, if you have feeders hanging in your yard, please fill the feeders.

MF: So there are many ways to support this citizen science project.

GS: Oh, yeah, for sure.

MF: One last thing I wanted to ask you was that you had the quote on your Facebook page that says, “everything you do teaches.”

GS: Yeah. So I've been doing this since I was a teenager. I worked at summer camps as a nature counselor. I've always been working with people, teaching them about nature. But, you know, we teach so much by example. So you say one thing, but you do something else. And the actions, as the saying says, speak louder than words.

And to me, working with young people in the outdoors and nature and developing a respect and concern and sense of stewardship is so important. I've spent a long time training and teaching young people, 19, 20, 23 year olds to work with people in the outdoors, working with kids in the outdoors, and particularly in summer camp situations where you're living right with the kids. So on one hand you say one thing, the other hand you do something. And, you know, I see it in schools where the kids and the teachers will be talking about solid waste problems, and then you go to the school cafeteria and they have plastic, disposable trays. It's like, you know, here we are, we're teaching the kids, we have this big problem with solid waste, and yet… The teachers don't have any say, it becomes a bigger issue because it's administration, it's budgets, you know. Washing dishes, washing trays, versus throwing trays out and things like that. So, you know, it's a tough nut to crack in some cases.

MF: Definitely. But teenagers are more sensitive around hypocrisy.

GS: Right, exactly. And some of them will start to pick up on it, which I think is a great thing to see. You know, some young people going to a school board saying, hey, we're concerned about this or can we do this? And, I mean, just looking at the food waste that gets thrown out and then that's landfilled instead of composted. And there are some young people, 14, 15, 16 year olds that are pushing for that in schools, like, “can we compost things?” and things like that. That's the kind of world that I hope to see where these young people become leaders and help make decisions that work for the whole environment around us.

MF: Well, thank you for your work supporting that positive change.

GS: Well, you're welcome. Thanks.

Bird-inspired Music of the Month

Tunes from Coyote Butterfly, a brand new release by Simon Joyner co-released by BB*Island and Grapefruit, and a field recording piece fox and cranes echoing by Mélia Roger & Grégoire Chauvot from harkening critters, a compilation released by forms of minutiae in 2024.