Beakuency welcomes Chris Funkhouser, a writer, musician, and multimedia artist based in Staatsburg, Dutchess county. Chris hosts the POET RAY’D YO radio program at WGXC. His latest project “Media Safari” documents his walks in the woods alongside the Hudson River. The natural sounds he captures that feature many birds and his writing on these “safaris” remind us to cherish each unique and ephemeral moment we experience in nature. He shares how curiosity and technology help us become more attentive and expand our perceptions.

Chris’ website: https://web.njit.edu/~funkhous/

Poet Ray'd Yo: https://wavefarm.org/radio/wgxc/schedule/ya0ah

This interview was broadcasted on July 27th, 2024 at Wave Farm’s WGXC 90.7FM.

Interview Transcript

Chris Funkhouser: Primarily I'm a writer. That's what my life has been about for almost 40 years. I do music and sound a lot now. But my real identity is in writing poetry specifically. I do lots of audio engineering with writers, and am an editor at PennSound, which is the largest archive of poets reading their own work online, at the University of Pennsylvania. I've been editing there for about 15 years, and that's very gratifying work. I've done these very extensive single author recording projects for PennSound. I don't write as much poetry as I used to, but I'm still heavily involved with it, working with other people, and the radio show too, Poet Ray’d Yo. It's all poetry.

Mayuko Fujino: That makes a good intro, because the first question would have been, “could you introduce yourself?”

CF: That's what I thought you asked me. I thought I already heard the first question.

MF: I sent it telepathically, or maybe you read my mind. Could you also say your name?

CF: Yeah, my name is Christopher Funkhouser. Born 1964.

MF: And you're currently a resident of Dutchess County?

CF: This is Dutchess County, Staatsburg. I've been in and out of this area for the past 10 years. We lived three years in Connecticut, which was partly responsible for my bird connection. It was the pandemic, so there wasn't a lot to do in terms of socializing, but if you live on a mountainside where there's lots of trees—we lived right next to a park, a big park called Tanager Hill—wow—sure enough, it was a great place to watch birds and hear birds. And the Farmington River was just below our house on this mountain, and Tanager Hill was right up and beside our house.

The other thing I do is I'm a cyclist. I ride my bike a lot, and in Connecticut there are many, many rail trails, many beautiful trails, and that's where I first identified the veery, on a rail trail. That made me happy. I heard that bird for two or three years before I could figure out what it was. It sounded like, well, Pat [Gubler, also present] was saying overtones, but also had this sort of percussive, cylindrical, wooden gding-gding-gding-gding, spinning sound, it’s beautiful.

MF: Very mysterious sound.

CF: Yeah. My interest in, my participation in improvisations and music has, I think, changed my relationship with birds because I used to be about the colors and the shapes and, you know, the spectacle of the sight of my favorite birds, all of which are wildly colorful. Then when we moved here I had access to so much nature. I can get energy from when I come out here and walk if I haven't had a hard bike ride. Every night, I hike at least a mile around these trails and I never know what I'm going to find. I have developed an appreciation for the residents, as you know, and I make a lot of recordings and some of them I use, and some of them I sort of keep in mind. We’ve been talking about the Indigo Bunting, and I love the song so much. I like the way it sounds. I like the way it looks on the app. The architecture of the sound on Merlin is so cool. It looks like Duchamp nude descending a staircase, horizontally instead of vertically. That’s just the app, I don't know how…

MF: When you say you like the look, you like the look of the sound wave?

CF: Exactly. I know this from my work in audio engineering. One of the authors I work with, I can't see what words he's saying, but I can tell a lot about his voice, and what he's doing just by the waveform, and the same is true on this app. You can tell the patterns. It's really patterning. I think that's what they must be doing in that spectrogram. They're somehow registering pitch and whatever. If something is syncopated, you can see it. If something is complicated, it's got all these weird angles. It's something I've become interested in. In fact, I wasn't really thinking about the bunting. I was so happy that there's so many around here, because it's a delightful bird. I wasn't really thinking about that in any profundity. Because of our dialogue, and when you asked for some of the recordings, that's when I was sort of looking more closely at what the sound was doing. Now I want to do some comparative studies, because as I was saying earlier, last night I was hearing different intervals of sound in the song that I hadn't noticed before, and a few weeks ago when the band [Most Serene Congress] was together and playing, I was mocking or making, I was imitating in a way. I figured out which notes that the bird was playing and then I was like playing along with that as part of it. And so, yeah, I've developed a relationship with the nature of this area, with a particular sound. I don't know how profound or important that is, but it's something.

MF: So a lot of these insights that you're talking about, you've gained through this project you call Media Safari. It started last year, if I remember correctly.

CF: I came up with this idea earlier this year in the winter and spring. I can't say that I'm going to stake my identity on it, or whatnot. It just seemed to be the right phrase to use because I’d begun this practice of going out often, several times a week with the recording gear, underwater recording gear, this little handheld field recorder, my phone, or whatnot. Yeah, Media Safari. I've been told it's a good phrase, so I'm going to stick with it for now. David Rothenberg says it's a good phrase and it works for me. The whole connection with safari and exploitation of African animals and that stuff, I'm not so sure about. And even when I talk about the activity as hunting kind of makes me feel uncomfortable because I don't have any experience on that level, but hey it is like going out into nature in search of who knows what.

Because in this case, you really never know. Some days, some evenings—a lot of my walks happen in the later part of the day, in the evening—and sometimes depending, I think, on which way the wind blows, I'll hear nothing. Like the birds are all in the leeward side behind a hill somewhere, and that's surprising. The next night I'll go out and there's dozens of them. I don't know why, I don't know about the patterns of performance patterns of birds. But it's been interesting and challenging. Like I say in that piece of writing, coming out here and making recordings has actually improved my ability to make recordings in the studio and at home, too, just because there's so many variables like the wind, and placement of the microphone, that can interfere with the fidelity of the recording. But I'm not trying to be Hi-Fi, I just would like to make good recordings, why not?

MF: So this piece of essay is going to be a part of your ongoing writing project. You describe practical things, like what your setup looks like and how you approach. I really love the way you wrote this essay. It's written in plain English.

CF: Thank you.

MF: So unpretentious, and there's nothing, no annoying academic thing about it.

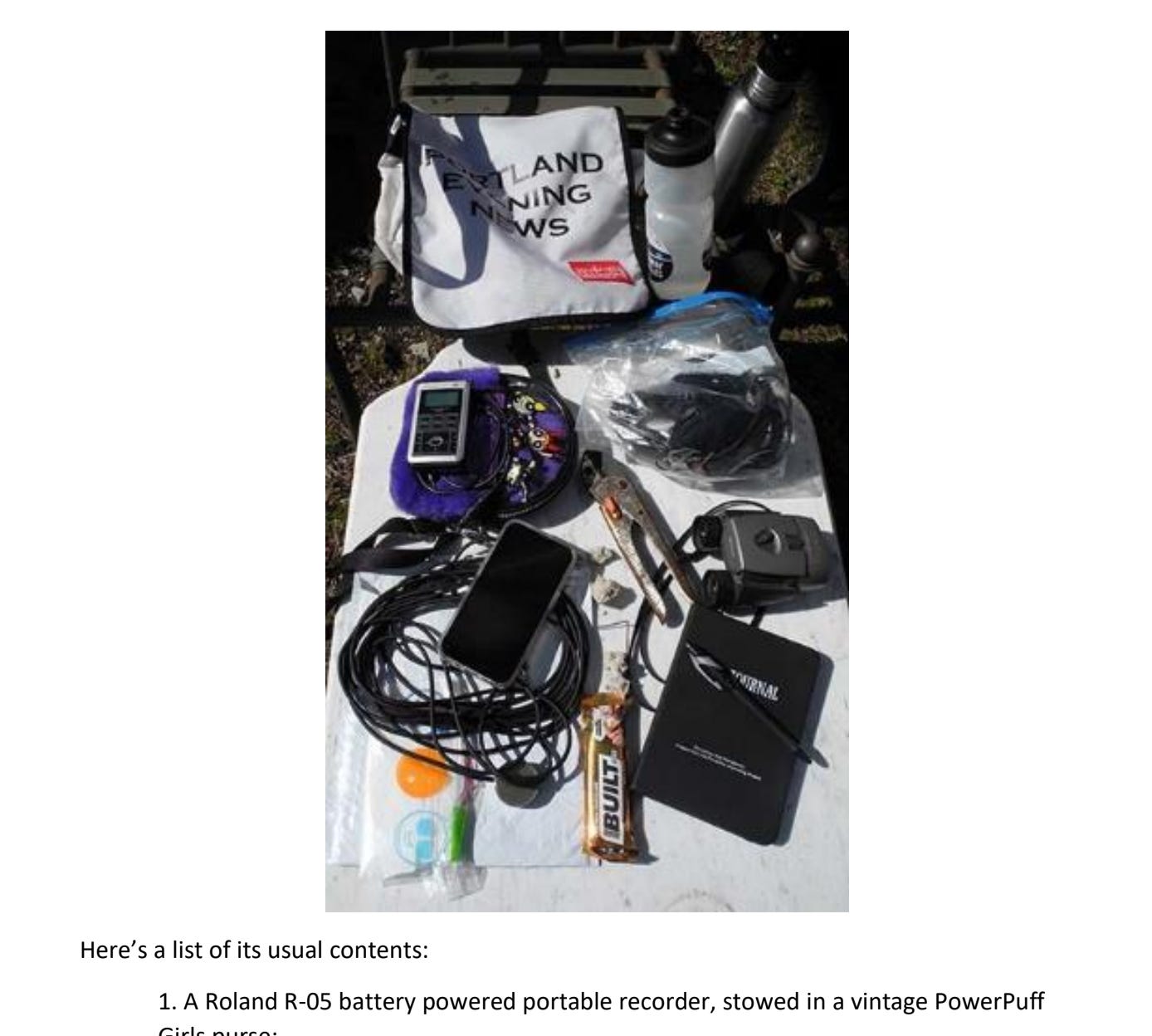

CF: That was kind of the point, right? This idea of making something useful. It's also important to be prepared. I was just out here taking regular recreational hikes, or for some exercise. When I realized that I was increasingly becoming involved with making recordings I had to be a little more prepared, and oh yeah, and I should bring water and food. Oh yeah, sunblock and bug spray and all these things. So then, I dedicated one bag, the media safari bag, and I should tell the readers what's in the bag.

MF: Right, you had a picture of the little pouch of Powerpuff Girls.

CF: Oh yeah my recorder is usually in this Powerpuff Girls bag. My kids like Powerpuff Girls, I like Powerpuff Girls, and I didn't throw that stuff away.

MF: So that's part of your equipment.

CF: Yes, and your comments are gratifying to me. That essay is the last chapter in this book that I'm just finishing. It's very different than the other chapters which talk about my work with computers and software and making documentary recordings and the history of audio poetry in this country. So then, it's just funny like that, where do I end up? I end up out in the woods making recordings. It's like Thoreau is finally taking hold of me, and there's more to it than that, because I do use the recordings for artistic purposes. And also to just inform my existence.

MF: It's all about how you made a little success and then how you made mistakes and you're trying to figure out what didn't work. And it's all, I bet, hard to figure out because there's so many factors, like the season, the weather, like you said.

CF: Yeah. Well, it's tricky making recordings outside, or it can be, and then so it's very gratifying when you do it right. Especially with the wind. My basic media safari setup is not with laptops and audio interfaces and all that stuff, but I can do that. I have the equipment to bring a real studio out. It's a big pain, but if I'm at a reading that's out in nature, that's the biggest challenge. When I can do it like in the beginning of June with Pierre Joris and recording him at T-Space. So amazing. I was so happy when that recording came out well. Definitely these field recordings I've been making helped with that very much high tech setup because, okay, note, the wind is coming from where? He's standing here. It's a very high powered condenser mic, so it's going to catch everything, including the wind. I don't have a pop filter. I don't have any way to filter that. So yeah, the fact that it came out so well is nice. So it's informing my larger practice, the sort of micro practice within that, for sure.

The birds are a bonus. Or whatever else I see. Turtles and frogs and snakes. I haven't figured out how to record them yet.

MF: I really like how you ended with this line that says, “as everything, the passing trains, water, birds, caterpillars, poets, recording devices, digital files, and the person making the recordings only ephemerally occupy space.” I think that was the last sentence of this essay. I thought it was quite beautiful. It made me think of this Japanese cultural concept that I've been kind of thinking about since I started really seriously birding. It's called Ichi-go ichi-e, and on the Wikipedia it explains it's a cultural concept of treasuring the unrepeatable nature of a moment. The term has been roughly translated as “for this time only” and “once in a lifetime”. It's an expression that reminds people to cherish any gathering that they may take part in, citing the fact that any moment in life cannot be repeated, even when the same group of people get together in the same place again. A particular gathering will never be replicated, and thus, each moment is always a once in a lifetime experience. This is sort of like a tea ceremonies and zen concept type of thing.

CF: I love that. That's great. I'm going to ask you more about that, but I will say the book that I've just finished is called Technicians of the Ephemeral. My view on digital media is that none of it's going to last beyond who knows how long, a generation or two, if we're lucky. So here are thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people making digital artwork. At least some of them have to know that the MP3, while we think of it is as a vital thing today, who knows where down the road. We just had this with Flash software. It was dominant 15 years and one day, bam, it's gone, none of that! It's this idea that flies in the face of this idea that life is short, but art is long, that famous expression, Keats’ Grecian Urn, this idea that our work now is not like Michelangelo's David. I'll be shocked, and won't be here, but to think that any of this is going to last seems… it's just transitory. This is kind of what this idea you presented, or you were just talking about, is about too.

MF: It's also interesting how it's linked to other things that you do, but I thought as you go through all these safaris in this essay, and every time it's different, your recording captures the uniqueness of each time you go outside.

CF: Absolutely. Well, anybody who does bird watching must be able to relate to that on some level.

MF: Yeah.

CF: I do know a couple places where the indigo bunting must be nesting. But still…

MF: It's different.

CF: Sometimes they're there, sometimes they're not.

MF: Right.

CF: As I said earlier, I'm not very sophisticated in any of this. I'm curious, and I feel like it helps me, grow somehow as a person. Not because I'm getting lots and lots of knowledge, but just to be able to situate myself in a context that's outside of myself or whoever I'm with, it's like it just expands life in a way. I mean, why do people watch birds? Why do people go out and look at birds? There's probably 50 million different reasons, right? Some of them are for the rare exotic bird.

I think when my dad probably liked to do that a bit, to go to a place where there were tropical birds. I am interested in the spectacle of birds, but it doesn't have to be that. We're lucky that there's some nice species—is that what you call birds? Different species? A cardinal is one, Robin is another?

MF: Yeah.

CF: We're lucky to be in a place where there are some really great birds.

MF: I really feel more and more that they're special to me because they're here and I see them. That living experience is like what's really special about it.

CF: Totally ephemeral, totally. This is a great thing that happened to me last week. I pulled up the driveway in front of my house and there was a great blue heron right on the pathway, right outside, right outside our house. I'd never seen this before. I was like, oh my god, and stopped the car and it didn't move. I got out of the car and was taking my time. I got enough time to get my camera out and take some pictures, it still is hanging out there, and then it sort of flew off. And I was like, well that was weird, I wonder what was up with that bird.

Then I was up at my desk an hour later and I saw the bird outside my neighbor's house. It was walking funny. I was like, oh, okay, maybe it got hurt and it just ended up over in our area. But then I noticed, I remember from seeing the great blue heron many times outside my family home, that when they're hunting, they have this very peculiar, slow walk, and it was hunting for frogs, out in the yard. That's what it was doing. It came here instead of being in the swamp, where you would expect to see a great blue heron and you would think they're hunting. But they were nowhere near any water, a little body of water or anything, but it had been so wet. There are tons of frogs. It was probably McDonald's [laughter], it could get anything it wanted right outside, and it was beautiful. I videotaped it, the whole bit. It was such a surprise, and I would not remember what I was doing at my desk, it was just an ordinary thing that became extraordinary because of this bird, they're like storks, right? They're big. Very dignified, like, “I am the boss”, and very princely or something, maybe that's not right, but elegant...

MF: I would also like to ask you about your music project, especially Most Serene Congress. I saw the video of the performance that was linked from the essay. I really enjoyed it. It's got a little bit of early Kraftwerk feel to the whole thing. Not only because of your flute, but the whole thing, and it was really enjoyable musically. You use lots of field recordings, your band improvises, you and your two other members improvise reacting to the field recordings or whatever each other is doing.

I thought it was interesting to see you switch instruments, from flute or you read some writings and then you play some little percussive thing. And every time you play something, you look like you're really listening. There was particularly this one scene I thought almost funny that you had this little percussion thing - I don't know what it's called - you hit it, and then you look like you're thinking, as if like, “what animal is this?” I was wondering if the way you pay attention to sound, is that how you've been always operating as a sound artist? Does this Media Safari type of practice that you've been doing, how has it affected you as a sound artist, if it has changed you in any way?

CF: Well, the reason I first met Pat [Gubler] was at Bobby Previte's improv workshop. Improvisation is something I've been interested in pretty much always. I can read music and I appreciate structured music, but I can't do it so well, and I'd rather not, as a matter of fact. I like making stuff up in the moment because of the surprise that offers. Listening, as we learned in our improvisation workshop—to be a good improviser you have to be able to hear lots of things at once and sort of filter it and respond. Instantly, or basically instantly. There's this great book, if you haven't seen it, newly published, called Quantum Listening, by Pauline Oliveros. It has been very appealing to me. You could pick it up at Oblong on your way out of town. It's complicated, right? A band! I'm just lucky to work with people who are willing to indulge these ideas of making recordings of water sounds or bird sounds or insects or whatever. These bugs or cicadas I have been recording them lately, and I'm sure we're going to play with them but that's going to be very different than like birds chirping, right? So I am listening all the time and trying to figure out. With the instruments? I just I like to play different instruments.

Most Serene started out as a noise band, two basses and a drummer, really pounding out kraut rock type stuff, improvising, then I throw the flute in with metal playing in the background, and it was nice, but we kind of grew out of that into something more electronic and droney. We don't use the drum kit too often anymore, those guys are on iPads, so the ambient music, the ambient type of drone with natural sounds has worked well to our benefit. We have this one indigo bunting song we most recently did. I'm rambling on about political stuff, and then all of a sudden it goes into the bunting, the little notes that I had sort of transposed. Those guys weren't aware of what I was doing, but they have to respond to it and it becomes something greater than the original intention.

There's no end to weird ideas for me. I'm 60 and the weird ideas just keep coming. You maybe even have this relationship with sound too, like where you take a shower, the water's running down the drain, and it sounds like an orchestra. So I record that, and then we'll throw that into the software as part of the mix. The technology, which is ephemeral, does give us a lot of liberty to experiment. That's kind of what this is all about, and I don't know what I'm doing. I'm just messing around. I know there's precedent for it. I know Zach Poff and Dave Rothenberg and, oh, the great Susie Ibarra. My goodness. Like the sound walks. And in 2015, I started really narrowing my focus into sound and music rather than doing lots of multimedia and the digital poetry research I did. That was about algorithmic generation of language. It was about hypertext, nonlinear writing. It was about visual writing. But now I've put a lot of that to the side and I'm focusing on sound. Everything has come together nicely. I find it to be gratifying and yeah, birds are a part of it because they have great sounds.

MF: Special things become special because you have ways and time to pay attention to it. Technology allows us to hear sound that we couldn't hear and we'd be amazed like how much stuff is actually going on, like right here, right now, just because we couldn't see it or hear it, doesn't mean it was not happening.

CF: I couldn't have said it better myself. Yes, you're absolutely right. The here and now is paying attention. This is the kind of what Pauline is getting at in her book. There's always so much sound, and the thing I noticed was, if you concentrate on it, you can really start to hear so many things with the technology, In that essay, I say, “we sure can amplify nature”, so that becomes a matter of attention, and just paying attention to what's around you. I'm not so sure that everybody does that. I'm not trying to throw shade on lots of people, but I see a lot of people looking at their phones all the time and so on and so forth. All well and good, but it does distract you from something else. I was lucky to grow up before phones and computers and Internet. Our parents sent us out after school, said come back at dinner time. I was able to develop a practice of being outside. Enjoy, find ways to enjoy doing it.

MF: Yeah, you wouldn't just know how. I don't think I, for one, knew how to pay attention to things, or let alone about hydrophones. I wouldn't have known there's such thing if I weren't involved in Wave Farm, and all the things people do for us to enhance our senses. So it's really cool to get to know what people are doing and hanging out with birders who really like training their ears. Very enlightening experience for me, and it's only happened in the past like five years or something to me.

CF: The other thing I want to say to do with depth of listening is I have tinnitus. A little over two years ago, I woke up one morning, my ears were ringing, and they haven't stopped. That sounds terrible, and when I dwell on it, it can be. But, two things. One is, there are ways to distract yourself from that tone. I'm talking to you and I'm not hearing it, but it's there. But, this area, I swear, in the summer, all the sounds that are here, and you're hearing now, we've just heard, there's the birds, there's the insects, I've heard some frogs right there, if we sat here long enough, you'd start to hear three, four layers of sound. This is helping my tinnitus! It's sort of unscrambling whatever that is. This is just a half-baked theory of mine, but last September, after being here for about a month and a half, I couldn't hear the tone anymore. I blamed all the frequencies of sound that were surrounding me.

So I think it can actually, aside from the health benefits of exercise and taking a walk and all that, there are other things we can get out of being in nature that are almost intangible, but yet very tangible at the same time.

MF: Yeah, very interesting.

CF: I've talked to doctors about this. They can't fix tinnitus, so you have to figure out ways to either hypnotize yourself not to hear it, which people do. I think meditation helps me with it a lot, because I'm able to sort of block it out. All the frequencies at night. Wow, in the summer nighttime here is so loud.

MF: Oh, it must be.

CF: With the frogs, insects. All that sound, and I sleep with the window open, my head's right at the window all night long. So it's sort of unscrambling the chaos, all that chaos, unscrambles the chaos of tinnitus, period. I just thought I should say that because I think there are benefits…

MF: Very solid benefits.

CF: …to absorbing sounds in nature, sights in nature. If you're lucky enough to have sight and sound, you know, why not use them?

MF: So this book, well this essay, about your Media Safari, you're finalizing the last chapter of the book right now. For those who want to learn about your Media Safari, should they wait for the book to come out? What's the best way for them to learn more about your work?

CF: The institutional website I have at NJIT is pretty good. That usually has up to date stuff. Look me up online, find my email. I'm happy to share with anybody who's interested. Plus, I imagine I can be reached through WGXC somehow.

MF: That's true.

CF: I don't have a WGXC email, but there aren't a lot of Chris Funkhousers out there, especially in Hudson Valley. I'm happy to engage and talk to anybody who's interested. I do the Poet Ray’d Yo show on WGXC. People can find me through that. I don't know about the book. Right now I'm finalizing the third draft of it. I've got other stuff to do, so I've been trying to do this. My next book is going to be about the radio show, as a matter of fact. I'm going to try to transport the content of the radio show into book format.

MF: Well, thank you for the great conversation.

CF: Thank you for coming out and spending time. It's fabulous to see both of you.

Bird-inspired music of the month

Most Serene Congress, the improvisational musical ensemble, of which Chris is a member, based in the Hudson Valley.