Beakuency welcomes Pat Walsh, the owner of Swamp Angel Antiques in downtown Catskill. The store gives us a glimpse into life in the Catskills over the past century. Swamp Angel Antiques is located in the Day & Holt building, which was built in 1818 and home to the Walsh family’s hardware business since 1912. Today, the space is filled with charming vintage hand tools, collectibles, and duck decoys.

Ducks have been a part of Pat’s life since his childhood days at his family’s hunting camp. The natural beauty of these birds is on full display in the form of decoys at his store, and Pat shares the history and stories behind them. He also tells us how the environment and regulations surrounding waterfowl and hunters have changed over time, and the role hunters have played in conservation efforts.

Swamp Angel Antiques

349 Main St, Catskill, NY 12414

(518) 943-2650

This interview was recorded on May 21, 2025 and broadcasted on Wave Farm’s WGXC 90.7FM on May 24, 2025.

Interview Transcript

Mayuko Fujino: Like I mentioned when I introduced myself, I'm pretty ignorant about hunting and guns and all that stuff. I was born in the suburb of Japan and spent most of my life in urban area. So many of my questions may come from an ignorant place. I hope you forgive me for that.

Pat Walsh: Oh no no, that’s fine.

MF: I wanted to ask hunters about how they look at the world, because bird watchers and hunters, they both deeply care about bird conservation, even though their relationships with birds are very different. So thank you so much for taking time today to speak with me. Could you briefly introduce yourself first?

PW: Yeah. My name is Pat Walsh, and I'm a lifetime Catskill resident. I worked in the family hardware business, actually, since I was in high school in the 50s, and then full time since 1962 with my brother in the business. My grandfather started the business in 1900 — He started working here in 1900 and bought the business in 1912. So I was third generation in the hardware business.

There was a hardware business here since 1818 when the building was built. And it turned over to a few owners since then. And the Day and Holt, which is our name now, bought the business in 1890… 1880, I think, about 1880. And then my grandfather worked for them, and then he bought the business in 1912 and expanded it with the building next door, and that was history.

MF: And you said your grandfather, or was it your great grandfather who came from Ireland?

PW: My great grandfather came from Ireland.

MF: So your grandfather was born here?

PW: Yes, in Catskill. We got out of the hardware business in 2006, mainly to get time off. You know, I was spending six days a week here all my life. It was very hard to get away for a vacation or do something else, you know, I always found time to go duck hunting in the fall, and I never really got into fishing because I never had the time and I never played golf because I didn’t have the time. But I kept the hunting part of it. And because of it, mainly because we had the camp on the river. And, you know, if it wasn’t for that, I may have drifted away from it also. But with that, it kept us. It's like a home away from home. And it was a beautiful spot. We spent a lot of time in the summer there, just hanging out and cooking and spending the night and stuff.

MF: And that's exactly which town?

PW: It's in town, it's actually a mile south of here on the river. Have you heard of the Ramshorn Creek? We’re 300 yards south of the Ramshorn Creek entrance, mouth. So I can be out my back door and my boat and be there in 10 minutes. So it’s very convenient. Some people have homes up in the Adirondacks and it takes some hours to get there. You know, I can be there in a few minutes.

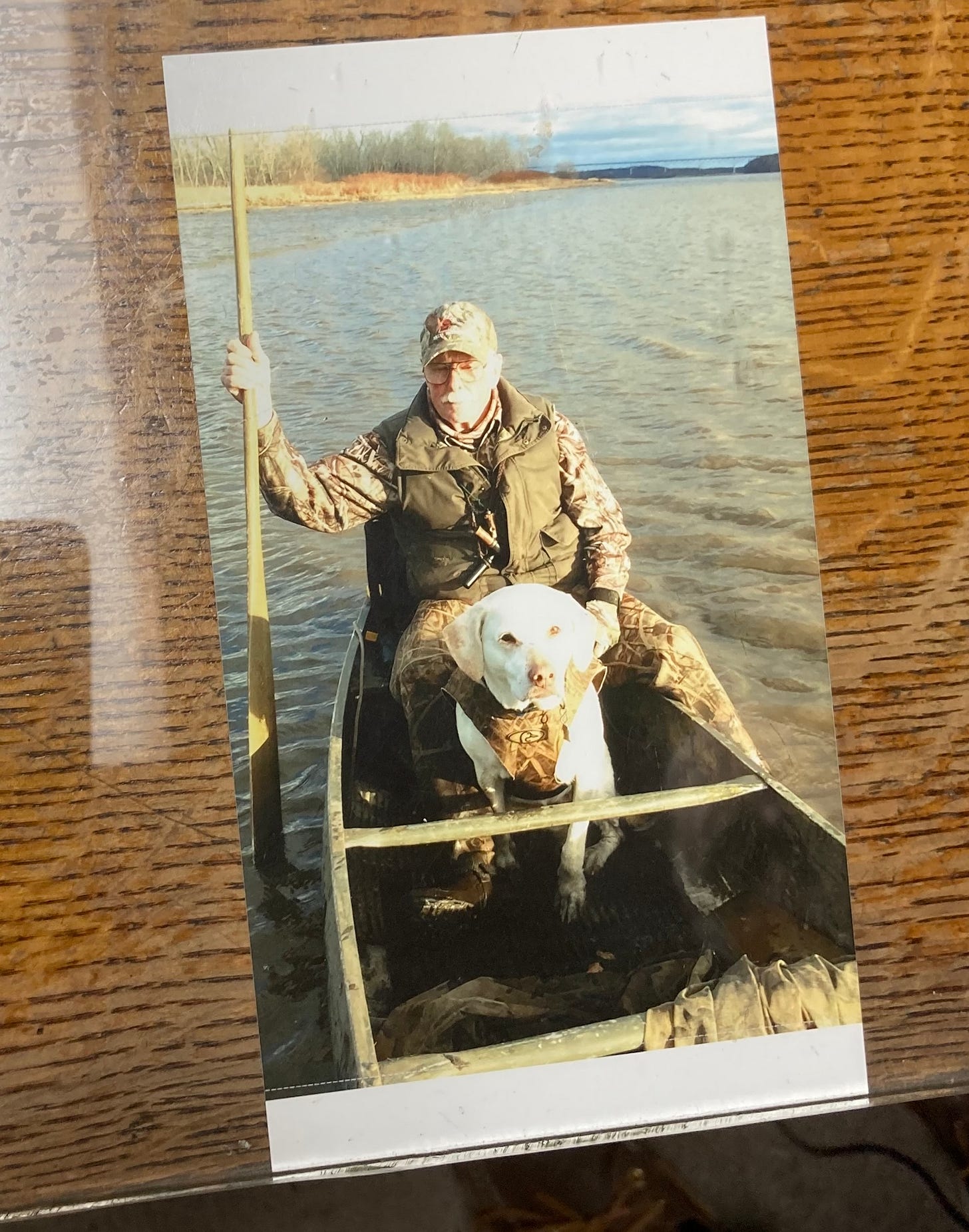

MF: And that photo is from there, too? We're looking at a picture of your family… you, your brother and your father in the… would you say [that a] canoe? A boat?

PW: That was a boat. They were made in Catskill by a guy named Brenner. And in the wintertime, from probably 1900 to 1925 or 30, he would build duck boats in the wintertime because he was slow on order. And that's what was one of them. We had actually two of those.

MF: There are a lot of duck decoys in the store. Antique duck decoys.

PW: There’s some. They’re both contemporary and antique.

MF: Have they been always part of your business?

PW: No, not the hardware business, no. When we morphed into the antique business, we decided to gravitate on the things we like, the old tools and the decoys. I started reading books on furniture, and I’d fall asleep, you know, trying to learn about furniture. I knew something about it, but, I mean, to really learn, you have to know things.

And the name Swamp Angel actually came from the names of the fellows at the duck camp. When my father bought the property back in 1949, he had a bunch of guys that hunted there, and they called themselves the Swamp Angels. So we gave the name. We decided to give the name with the decoys and stuff to the Swamp Angel Antiques.

MF: And I saw there were some name tags displayed with each batch of duck decoys.

PW: Those are carvers, known carvers. And some aren’t, I mean, some are, nobody knows who carved them because they just were carved and used, and then they were collected or didn’t get thrown. Just a little background, but in 1918, the United States passed a migratory game law that prohibited market hunting. They waited that long because Canada wouldn't go along with them, I think that was. So it wouldn’t be much sense if United States did it and Canada didn’t do it, you know, didn’t pass a law to control market hunting. And after that, the market hunters used to use hundreds of decoys to attract ducks. So a lot of these guys just, you know, put them into firewood, that was it. They had no use for them anymore. So in the early time, the decoy collectors back in the 50s and 40s, they would go around and pack their vans or their station wagons with plastic decoys and go around and trade them for wooden decoys. And they were ahead of their time because a lot of these guys didn't care about the wooden decoys. They were in the shed out back. And in fact, I grew up hunting with wood decoys, and I didn’t like them because they were so heavy. You had to move them in, move them out in the boat. And so when the plastic decoys came out, you bought plastic decoys. They were relatively cheap, and just use them. And they look probably better than some of the wood decoys. Anyway, that was the deal with decoys back then. A lot of the carvers today actually use their decoys to hunt with, and then they sell them after they use them. Or, they also make them to sell.

MF: When you say marketing hunters, those are the people who hunt…

PW: They would hunt strictly for the market. You know, they would kill hundreds of ducks a day.

MF: So this is for consumers.

PW: For consumers. And they ship them in ice to the metropolitan areas, to New York, wherever the closest city was. They'd be all packed in barrels on ice. And 150 years ago, back in the mid-1800s, for certain species, ducks, Canvasbacks mainly, they would get a dollar a pair, and that was a week’s salary for somebody for a couple of ducks. I mean, it was hard work, and they did it at night. They slaughtered ducks actually, back then. But at the time, they never thought they’d run out of ducks because the sky would blacken with them, when they migrated. But some of the hunters back then started being concerned because they noticed that some of the ducks weren't as plentiful as they were. So they started promoting conservation because they knew. Trying to get the politicians to set limits, set times when they could hunt. And so that morphed into that, and of course, the old timer didn't like that at all.

MF: Okay, so [market hunting] ended really because of the conservation concerns.

PW: Oh, yeah. They knew they were going to run out of ducks if they kept doing it. And in fact, a couple of species were actually eliminated, you know.

MF: Well, okay, thank you. Going back to the decoys, I wanted to ask more about the decoys. The ones you carry now in the store, how do you find them?

PW: Well, most of our decoys, we bought at auction. We went to decoy auctions. We’d go to three decoy auctions, three or four decoy auctions a year. One in Jersey, one in Cape Cod, and one in Maine. And that's where we bought most of our decoys. But they also had what they call tailgating. You know, the dealers or people would have decoys for sale. They would be there at the auctions, and you could buy them there from them. There were also carvers that you could buy them from, contemporary carvers, obviously. But generally, we waited for the auction. And when we first started, we were terrible. I mean, we’d buy stuff that was junk almost. We didn’t know anything about it. We started around 2000, we started going to auctions. And the first few, we learned very quickly not to buy the junk. I say junk, at the time it looked okay, but we didn’t research enough. We didn’t know a lot. And we learned pretty quickly that, to be a little more discretionary and pick certain decoys out and try to buy them at a certain price.

MF: What makes it a junk decoy?

PW: Well, it's been beat up, it's been painted a bunch of times. I picked up one after one of the first orgies we went to, and we went to pick up the few we bought, and we didn’t have a lot of money then either, we don't have a lot of money now, but, you know, but we were caught up in it. And I always had decoys. And when we got into it about then, and we started collecting ourselves and we were buying also for resale, so you had to try to buy them at a price you think you can resell them at also.

MF: There are many different artists with unique style.

PW: Oh, yeah, they all have their own actual style and the way they carve. But, the first thing I tell people, if they’re going to buy a decoy out there is, you got to like to look at it, you know, when you walk by it. If you buy it, you want to be able to smile when you see it, because it’s attractive to you. It may not be attractive for me, but, to you, it's attractive. And then you try to buy it if it’s been not over painted, original paint. And then you look at maybe the carver, I collect certain carvers because they’re good, their promenade is there and you like the looks of them. And the structure, I guess the structure is important too, not banged up or broken. So those are the four things you kind of look for. But the main, the first thing, though, you look at it and you like it.

MF: What kind of duck decoy do you think would speak to you personally? Is it something you can verbalize?

PW: Well, I gravitate toward the decoys that we hunt, the Mallards, the [American] Blackducks, the teal, the Wood ducks, you know.

MF: So when you choose decoys, that's one of the things that attracts you, that it’s the species being part of your life.

PW: To me, yeah. I mean, I'll look at anything, [for example] Canvasbacks, we don’t see many of them up here. but some are beautiful, you know, so you do collect other ones. But again, if I’m generally collecting something, it’s something that we hunt around here anyway.

MF: Duck species sighted in around the Hudson Valley has changed a lot over time?

PW: Hasn’t changed a lot, you know. Although when I was growing up, we hardly ever saw geese here, on the river anyway. Sometimes they lay in the fields on the way through. But now there’s geese all over the place. But Wood ducks are the most prominent duck. Native duck. And there’s Mallards and the teal they migrate through. They don’t really nest here. Diving ducks are usually prone to big water, you know, there’s not a lot of big water here. I don't know why they don't come right down the Hudson Valley to get south. But they seem to gravitate to the shore, I guess the ocean, for some reason, because this isn’t a big flyway. We had our share of ducks, but not what you think you would.

MF: I wanted to ask you also how you started hunting, but I guess your family had been hunting.

PW: Basically, yeah. My father got that camp. I grew up down there getting firewood and just hanging around down there doing work or doing whatever had to be done. And then I started hunting when I was 14. We stayed at the camp. We'd be — myself and the other couple other kids, my cousin — we had to sleep on the porch. And all the guys were inside, the adults were inside playing cards and they got the bunks inside. And it was just, that's what you did, when you grow up. We grew up, I guess if you didn't have something to do, you were put to work, basically. So you knew that it was better to be working down there than hanging around the house doing something else.

MF: Do you remember how old you were the first time you shot a duck?

PW: I was probably — when I was 14. I remember first time I shot a shotgun I was probably about 10. And my father and uncle owned the boatyard down here, which wasn’t much of a boatyard, but it was at that time right in the village and they gave me a shotgun or we were down there and they were shooting at the across the creek. It almost knocked me down, you know. I mean it wasn't a big shotgun either, but it got my attention.

MF: Were you afraid?

PW: No, never was afraid but didn’t know what was going to happen. But I didn’t think it was going to do that, you know, hammering my shoulder.

MF: And then you have to learn how to dress them… is that the word, dress the bird?

PW: Oh yeah, yeah. It was one of my jobs. Back then, we dressed the whole duck. Now what we do is, we just take the breasts to eat, it's 75, 80% of the meat and the rest is just not, you know, this isn’t worth the effort to me. But obviously, 100 years ago they ate every little bit, because that was it.

MF: And so when you first shot the duck, you also dressed the duck yourself, or you had been doing that [part] already?

PW: Oh well, yeah, he showed me. I dressed most of the ducks at the camp at the time. You plucked them. Well, first of all, you take their innards out, you'd cut them, peel that feathers off there, then you'd hang them. And then when you took them home the next day or so, you would dress them out, you know, pluck them. And my mother used to tell me — because you had to pick out the shot in them too, the bird shot — my mother used to say, don’t bring them home unless you shot him in the head. You could see him sit there trying to get the steel and that’s another bone to contention. We used to use lead shot, obviously, and it’s a good thing that he went to steel shot. But the problem there is, if you bite into a lead shot, it's a little forgiving. But if you bite into a steel shot, the dentists are happy to see you because they're going to probably break a tooth.

MF: I’ve heard of people concerned about the lead bullet. What exactly is the issue?

PW: I don't think lead bullets are lead shot. When it was shot over fields and stuff, the birds, waterfowl especially, they eat grit to clean their gullet. It gets in their gullet and cleans their gullet. And if they pick up lead shot, and then it's going to eventually dissolve and maybe kill them or hurt their health anyway, certainly. And that was in primaries, I don't know over water what it would do. But the lead was pretty minority. It's not going to dissolve really. But your acid would dissolve in a bird’s stomach. I don't know. It’s a good thing, don't get me wrong. It had to be done. But the non-toxic shot, it was a learning curve too, because when they first came out with steel shot, I had old shotguns and I couldn’t shoot the steel shot through it because it would hurt the barrels because they’re softer barrels. So I had to go out and buy a new shotgun. I bought a cheap shotgun just so I could go hunting with it.

Learn more: “Waterfowl Diseases - LEAD POISONING” by John M. Coluccy, Ph.D., and Nathan Pfost, Ducks Unlimited

MF: I see. So that must have been the obstacle for people to switch from lead shot to steel.

PW: It was different at the time. Especially then the ballistics and everything were bad. You know, you’re getting a lot more crippled ducks because people were shooting at the same ranges and they really weren’t deadly at certain ranges then because the lead shot had more impact. So, again, that’s another learning curve for the hunters. And then you got a lot of inexperienced hunters that shoot too far anyway. I always tell anybody I’m with, make sure they’re in range. You know, if they’re more than 40 yards out, don’t bother shooting or if you do, you’re just going to hurt them.

MF Do people shoot too early because they’re too excited?

PW: Well, too early, maybe they didn't even get close enough. You know, a lot of reasons, excited or they just think they can get them.

MF: You no longer hunt?

PW: No, I stopped two years, three years ago at 82.

MF: Oh, that's recent.

PW: Oh, yeah. I mean, because I'm aging out, you know, I'm unsteady on my feet, and I can't be walking around in the mud and whatever.

MF: Oh, that's impressive, though. I don't know if I can do it now.

PW: No, I grew up doing it, you know, I used to walk miles through the swamp every day. But no more. I’ve gotten to the point where I don’t really want to kill anything anymore, too, I’ve done that, did that. You look at it a little differently as you get older. You know, your mortality shows you, I guess, slows you down. I don’t know. It’s different.

MF: It’s interesting because some people think hunting is cruel. But then other perception of hunters [is that they are] in touch with the natural world in a more raw and intimate way. And the way I look at life, I've been in an insulated world where I don’t have to see animals being killed, even though I eat fish. I love eating fish, I'm not a big fan of meat, but I do eat meat. And so I don't know honestly what to think of taking life away and eat them, because I’ve been sort of protected from [it], I didn't have to think about those things. How would you feel about that? If you had any thoughts… did it have any impact on you, [to] really think about you killing something?

PW: You know, the thing is, I grew up in a time where it was a natural — not a natural, but, you know, everybody did it. I used to go squirrel hunting, rabbit hunting, and I brought them home and we cooked them, and it was an adventure almost to go out. And [it’s] a skill to be able to harvest the game. What really bothers me is when people just go out to kill it, they don't care, they just leave it. I've seen people do that, and it really drives me crazy. I mean, that kind of person shouldn’t be out there at all for whatever reason.

MF: It is hard to relate to, especially, trophy hunting type of thing.

PW: No, I can’t. No, I mean, they’re killing, they’re not hunting. They’re… I don't know what the mentality is.

MF: I think the other image that people have about hunters, and I think it’s not just image, it’s a fact that hunters [having] played a role in bird conservation efforts. Would you be able to tell us what you think [they] have done in terms of [conservation work]?

PW: Well, I'm going to give you this book [hands over a magazine] You can read through it. You can see some of it, this is a Ducks Unlimited book. You can have that.

MF: Oh, thank you.

PW: Well, Ducks Unlimited and Delta Waterfowl are probably the two major migratory conservation groups that are out there, and there’s a lot of other ones, but those two are really in the forefront. They have a magazine that they send. They are, first of all, they’re conservationists, and they’re also restorationists. They spend almost all their money on restoration — restoring wetlands for habitat, you know. And you'll see some of the figures in there [in the magazine] that donate, they're very wealthy people that donate lifetime, whatever they call it, millions of dollars or a billion dollars to them. And there’s also farmers that get involved. And they go in and restore their part of their farm out West, Midwest, mainly in the Midwest. There's the prairie, as they call it, the prairie pothole country where the majority of the ducks in the United States breed. And they're affected by dryness. You know, if it's very dry, they [conservationists] try to curtail the predation by not eliminating the predators, but making it hard for them to get to the ducks.

MF: I also imagined that, to work on water quality improvement must be part of wetland conservation.

PW: Oh, yeah, sure.

MF: Those have direct positive impact, not just on birds, but people’s lives, too.

PW: Well, when I grew up, there were a lot of ducks around, you know, not like they were 100 years ago, but, what happened is the natural food for the ducks, the wild rice and stuff, got eliminated, got bumped out by the invasive species, your cattails, your phragmites, your Japanese knotweed. So the wild rice went away. And the other thing that killed was, especially back in the 40s and 30s and 50s, is that these tankers that you go up the Hudson river to Albany, they would come out, come down, and they would flush their bilges after they'd done. And I used to see oil slicks on the — not thick oil slicks, but in the weeds all the time when I was a kid. And you don’t see that anymore, obviously. It was illegal then, but they still did it because they didn't want to go in the ocean and flush it with salt water. They wanted fresh water flush. And again, that was a big thing to me. It bothered me then, but that pretty much went away. I think they monitored it a lot better somehow.

MF: Have you ever practiced duck calls? We were just listening to a record of instruction [on] how you can do the duck calls. It's like learning a whole language.

PW: It is, it is. I'm not very… I mean I can do it. [chuckles] This is, [takes out a duck call] well, originally a fairly inexpensive duck call. This is brand new. But really to me it seems a nice call.

PW: The funny thing is I never really started duck calling until maybe 25, 30 years ago. Because when I grew up, my father said, if you don't know how to call, you’re going to scare the ducks. [laughs]

MF: [laughs]

PW: So I said, well, I don’t know how to call. So I never really learned. And back then, the duck calls weren’t as good as they are today. I could never make them sound like a duck.

MF: I'm just so fascinated because some birders are really good at imitating bird calls and they learn how to do it. And some of them are really convincing. And the hunters having to learn the speech pattern of ducks, I like when people doing that, because I came to the United States not being able to speak English and it was so hard to learn somebody else's language. And then to see people making such efforts to learn even non-human language, it's just…

PW: Well, there’s a lot to it. I mean, again, it’s a lot of fun too, especially if you can attract the duck. But you think you're doing the right thing, and earlier in the season it’s easier because the ducks aren’t used to [it], you know, they aren’t as wary. You know, it’s like everything else, the smart ones are smart.

MF: That's another thing that’s fascinating. I was reading [about] how you can have many strategies to place decoys, in the V shape or whatever shapes. And throughout the season, ducks start learning it. And they’re not gonna be tricked easily as much compared to earlier [in the season.] I mean, those are really fascinating. They're pretty smart, I guess.

PW: Well, yeah. I mean, and they're survivalists. It's like everything else. They want to live till the tomorrow too. And they have enough to worry about predators and other things that are going after them.

MF: And so on the hunter’s side, you have to keep thinking that, “okay, this V shape no longer work. What am I going to do next?”

PW: I’ll tell you the truth. When I’m hunting out there and I’m in the blind, if I don’t shoot a duck, it’s not a big deal. It’s more being out there and doing it than the rest of it. We paddle, and I hunt the duck blind in the morning until, you know, 9 o’ clock, then 9:30, then we go back to camp and have breakfast, which is nice. That’s always nice. Otherwise you’d be out there all day with nothing, you know.

MF: Well, thank you so much for the wonderful interview.

PW: Well, I hope it works out.

MF: Oh, it totally does.

(Thanks to Pat Gubler for shooting these videos!)

Online-Only Content: Duck decoys made from recycled materials

MF: So this is very old, I guess.

PW: Yeah, that’s very old. Cork.

MF: That’s why it looks like that!

PW: Head’s pine, probably. Cork was big, in Long island, it was really big. It was big here on the river, too. What they used to use is old life jacket cork. And they used to find it on the shore all the time and just work around. That’s valise cork. It was cheap. They found it. They didn’t cost them anything, so they may used what they use. This is also cork. This is a L.L. bean.

MF: I like how the materials, people found way to reuse.

PW: It’s amazing, the stuff they use. There’s rubber decoys up there.

MF: Rubber!

PW: They use anything… paper.

MF: Paper!

PW: They coated it. They stuffed canvas. Those other ones are like cardboard, you know.

MF: Oh wow! And that can trick ducks? You think they get tricked by it?

PW: Well, it didn’t take a lot to attract a duck. Wasn’t a lot of pressure on them.

(And, a vintage flapping decoy!)

Bird-inspired Music of the Month

Recordings made in the United States for the commercial consumption of people engaged in hunting culture between the years 1947 and 1959, released by Canary Records in 2020.